1. Questions

During episodes of regional air pollution—such as from smog or wildfire smoke—public health and transportation stakeholders try to induce travel behavior changes through air quality alerts (Teague, Zick, and Smith 2015; Cummings and Walker 2000). In response, do people (1) drive less to reduce emissions, (2) avoid exposure by walking less, or (3) carry on as usual?

Population-level analysis of multimodal traffic over time can provide an answer to these questions. Yet, most prior studies examine only one mode at a time (Acharya and Singleton 2022; Doubleday et al. 2021; Saberian, Heyes, and Rivers 2017; Tribby et al. 2013; Welch, Gu, and Kramer 2005), making it difficult to know whether mode use shifts and/or volumes fall across all modes. Similarly, although locational contexts likely shape responses, few studies have modeled spatial variations in air quality–traffic relationships.

To address these gaps, we ask two questions:

-

What are the aggregate effects of regional air pollution levels on pedestrian volumes, automobile traffic volumes, and transit ridership?

-

How do the air quality–traffic relationships vary across locations (spatial heterogeneity)?

2. Methods

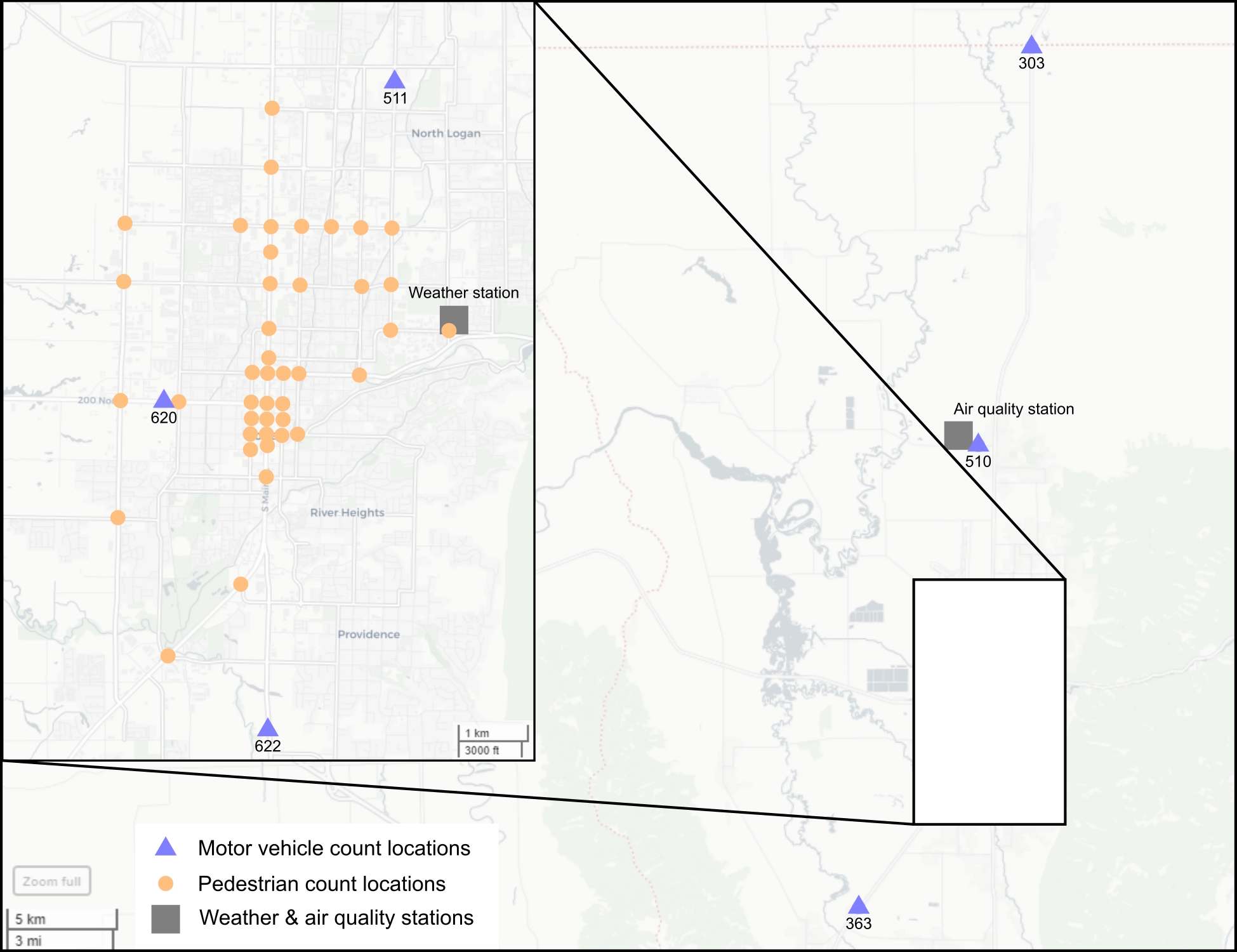

The study area is Cache County, Utah, United States, with a 2020 population of 133,154. The high mountain valley’s bowl-shaped terrain contributes to episodes of regional air pollution, specifically high particulate matter concentrations caused by wintertime temperature inversions and summertime wildfire smoke. Prior to and during such events, Utah government agencies issue air quality alerts (Utah DEQ, 2022) and encourage people to carpool, trip-shift, ride public transit, and telework (UDOT, 2022). These messages are often shared in local media.

We assembled daily time series data, from January 2018 through December 2019, for the following key variables:

-

Daily pedestrian crossing volumes at 39 signalized intersections, estimated (Runa and Singleton 2021) from traffic signal push-button data.

-

Daily automobile traffic volumes at six continuous count stations operated by the Utah Department of Transportation.

-

System-wide daily bus boardings (no rail service) for the entire Cache Valley Transit District public transit system (no service on Sundays).

-

Daily air quality index (AQI) at one station, based on concentrations of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. AQI was categorized by color: green = 0–50, yellow = 51–100, orange = 101–150, etc.

To address question 1, we estimated separate, mode-specific log-linear regression models of daily traffic, predicted by AQI category. We accounted for weather and other temporal effects by including control variables for precipitation, temperature, season, day-of-week, and holidays. To address question 2, we estimated these as multilevel (mixed effects) models, with daily observations nested within locations. For pedestrian volumes, we used random intercepts, predicted by built and social environment variables, and random AQI slopes; we also tested cross-level interactions to link slope variation to location characteristics. For automobile traffic volumes, we used fixed intercepts and fixed AQI slopes, due to the small number of locations (six). For transit ridership, we could not estimate multilevel models due to only having system-wide data.

Study locations are shown in Figure 1. Further details about the data and analyses, including descriptive statistics, are included in Supplemental Information.

3. Findings

Table 1 presents results for question 1, about the aggregate effects of regional air pollution on multimodal traffic volumes.

Overall, on days with worse air quality, pedestrian volumes decreased, automobile volumes increased, and bus ridership showed no significant change. Relative to green days, on average, pedestrian volumes were 5.2% lower on yellow days and 12.7% lower on orange days. This pattern is potentially explained by exposure-avoidance behavior: people walk less as AQI worsens. Compared to green days, on average, automobile traffic volumes were 5.1% higher on orange days, but not significantly different on yellow days. This increase with higher air pollution contradicts stakeholders’ hopes that air quality alerts reduce driving, but it is consistent with exposure-driven mode substitution behavior away from outdoor/active modes. System-wide bus boardings appeared to decrease slightly (by 7.2% on average) on orange days compared to green days, but this change was not statistically significant. Aggregate transit ridership responses may be limited by service design, trip purposes, or transit dependence.

Figure 2 shows spatial variations in relationships between AQI and pedestrian volumes (specifically, posterior slopes (Snijders and Bosker 2012)), thus helping to address question 2. Locations with more negative coefficients—indicating a larger deterring effect of air pollution—seem to be located in more peripheral or suburban areas, including to the east near a university campus.

Considering cross-level interactions with AQI, several built and social environment variables were significant in the pedestrian model. Higher car ownership led to larger pedestrian declines on higher pollution days (especially yellow), which is consistent with substitutions away from walking where cars are more available. Also, higher car ownership could signify higher income groups, who may tend to use cars on polluted days (Kim, Ko, and Jang 2023). Conversely, more commercial land led to smaller pedestrian declines on poor-air days (yellow), consistent with walkable destinations being closer and trip necessity higher in mixed-use areas. Similarly, in areas with greater street connectivity (share of 4-way intersections), we found smaller pedestrian declines on orange days, consistent with resilient pedestrian networks supporting shorter, more direct trips even when air quality is worse (Tal and Handy 2012).

For automobile traffic volumes, we did not find significant spatial variations in the AQI slope, potentially because there were only six stations. We could not evaluate spatial heterogeneity in transit ridership because only system-wide data were available.

In summary, observed patterns in this study region suggest that current strategies like air quality alerts are not reducing driving; instead, people are driving more and walking less. To encourage more healthy travel behavior change during episodes of regional air pollution, stronger policies may be required, such as mandatory employer-based programs like carpooling or telework.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted with support from Utah State University and the Mountain-Plains Consortium, a University Transportation Center funded by the U.S. Department of Transportation. The contents of this paper reflect the views of the authors, who are responsible for the facts and accuracy of the information presented.

_yellow_(aqi___51--100)_and.png)

_yellow_(aqi___51--100)_and.png)