1. Questions

The societal costs of an automobile-centric society (Litman 1995) and the seeming inability to make significant progress in shifting to more multimodal, accessible mobility frustrate practitioners and advocates alike (Weingart and Schukar 2023). This is despite decades of research providing evidence about policy, programs, and design that could reduce dependency on cars (Dill 2009; Elvik and Goel 2019; Handy, Cao, and Mokhtarian 2005; Pucher, Dill, and Handy 2010) and that dependency’s subsequent negative health, economic, and equity outcomes. Implementation, however, continues to be a challenge in the United States and other countries with autocentric transportation systems.

Travel behavior is not merely objective or rational in the economic sense (Groeger 2002). There are aspects of vehicle design and the larger transportation system that cause or exacerbate human emotions, biases, social stereotypes, and willingness to behave interpersonally in ways particular to the roadway (Abrahamse et al. 2009; Coogan et al. 2014; Delbosc et al. 2019; Diana and Mokhtarian 2009; Goddard, Kahn, and Adkins 2015). There is a need to understand how these psychological factors result in the inability to see beyond the literal and figurative windshield to envision different ways of doing things or generate the political will and public demand for change. Referred to variously as “windshield bias,” “car brain,” “car culture,” “auto dominance,” “American’s obsessions with their cars,” etc., Walker, Tapp, and Davis coined the term “motornormativity” (Walker, Tapp, and Davis 2023) to describe this phenomenon. In their study of attitudes among UK adults that contrasted social norms around car externalities to parallel, non-car social effects, they found robust evidence that people excuse the negative effects of car use in ways that obscure the public health hazard posed by an autocentric society (Walker, Tapp, and Davis 2023).

To explore whether adults in the United States hold similar attitudes, this study posed the following questions:

-

Do adults in the United States hold disparate social norms around public space, behavior, and property related to cars and driving?

-

How do these social norms compare to the original study of UK adults?

2. Methods

This study used a traditional replication approach, a valuable tool for building an evidence base (Nosek and Errington 2020; Simons 2014). The survey included ten statements adapted from the ten statements in the original motornormativity study (Walker, Tapp, and Davis 2023), with slight grammatical changes (see supplemental materials). Participants answered only the car-related or non-car-related questions via random assignment. Respondents did not know there were two versions of the survey, and the introductory description was written deliberately to describe the survey accurately but without any explicit discussion of cars and driving.

Participants were recruited via Prolific.com, resulting in 403 participants representative of the US population by age, gender, and ethnicity. Each participant received a survey incentive of $1.00, which amounts to approximately $12/hour for the five-minute survey. The random assignment by Qualtrics as participants elected into the survey from Prolific resulted in the following two groups: car group, n=214, 53.4%; non-car group, n=187, 46.6% (chi-square 1.818, n.s.).

3. Findings

Comparison of Attitudes Toward Car versus Non-Car Social Norms in the United States

Participants demonstrated diverging attitudes between car-based and non-car-based norms on every measure (Table 1). On the questions that relate to personal versus societal responsibility (i.e. on the questions about police response to theft or risk on the job vs driving), people were significantly more likely to respond in what could be characterized as autocentric attitudes. On the questions related to excusing negative externalities (i.e. rule-breaking, accepting consequences to society, and second-hand emissions), once again respondents were more likely to excuse negative car effects. On the second-hand smoke/emissions question, nearly 94 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that people should not expose others to their secondhand smoke, while fewer than 20 percent agreed or strongly agreed that people should not expose others to their car exhaust. Using an independent-samples t-test with a Levene’s F Test to compare mean responses to these questions based on which survey the respondents completed demonstrated statistical significance on every measure, all in the autocentric direction (Table 1).

Removing the ambivalent answers (neither agree nor disagree) and collapsing the remaining responses into a binary of agree and disagree, the attitudes about rule-breaking between delivery drivers and chefs show less divergence, as do the attitudes toward acceptance of consequences of driving and alcohol use to a lesser extent. The disparities in attitudes toward theft, acceptance of risk, and second-hand emissions when they involve a car, however, are stark (Figure 1).

Using these collapsed (i.e., binary, no neutral) agree/disagree measures, Bonferroni-corrected chi-square tests demonstrated statistically significant autocentric differences on all measures except the question about whether rule-bending by a delivery driver or chef is acceptable (Table 2).

Comparison of Car versus Non-Car Social Norms in the United States versus the United Kingdom

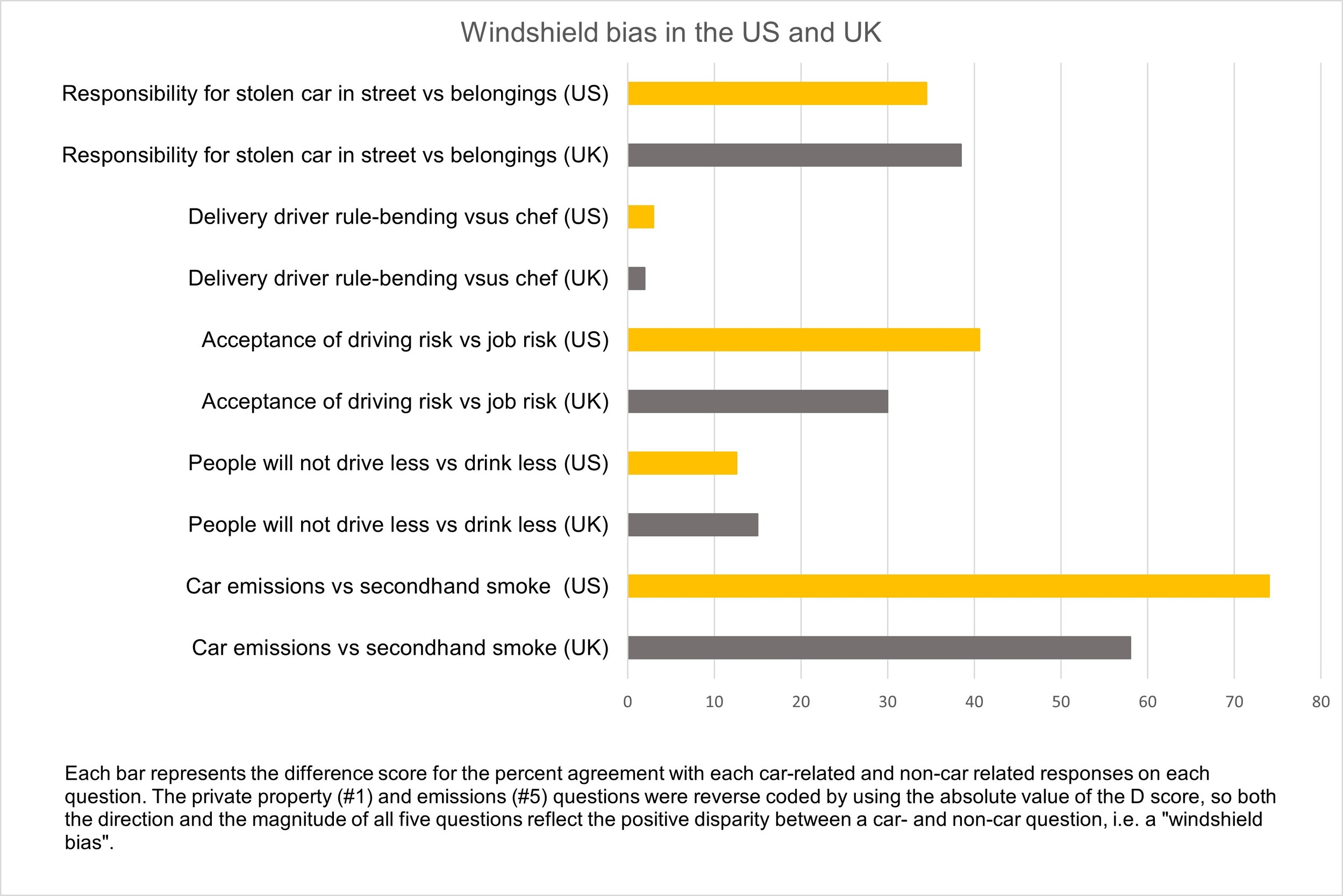

To compare the social norms found by Walker et al with the current study, a difference score was created between the car and non-car responses to each question. For ease of visual interpretation (Figure 2), the private property (#1) and emissions (#5) questions were reverse coded by using the “disagree” answers, all other questions use the “agree” answers. Thus, the magnitude of each bar reflects the windshield bias represented by the disparity between the social norm on the paired car- and non-car questions.

Social norms among the US survey respondents showed similar patterns to the UK respondents, with a windshield bias (i.e. positive difference score) on all five measures. US respondents were slightly less likely than UK respondents to hold disparate norms around private property or society accepting the consequences of driving versus alcohol use. US respondents, however, were even more likely to hold a windshield bias on the questions regarding the need to accept the risk of driving versus alcohol use, and whether people should avoid driving or smoking in highly populated areas where they would expose others to their secondhand emissions. Both in the US and UK, people held relatively consistent views (i.e. small difference score) on whether it is acceptable for delivery drivers and chefs to bend the rules for the efficiency of their businesses.

This study demonstrated that adults in the United States hold disparate attitudes toward private property, rule-bending, risk, consequences, and externalities when those issues concern automobile use. The terms “windshield bias” and “motornormativity” describe this phenomenon and how a system built around private automobiles not only creates automobile dependency, it also engenders further demand for autocentric ways to fix its problems. How the windshield bias and motornormative social norms displayed in this study translate into behavior or support for policy, programs, design, and investment is worthy of future study.

Acknowledgements

The Texas A&M University Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) determined that this research met the criteria for Exemption in accordance with 45 CFR 46.104, STUDY2024-0739.