1. Questions

Access to formal driver education and training with professional instructors (DT) is both a safety and a mobility equity issue for teens in the U.S. In terms of safety, consider outcomes in Ohio, a state with Graduated Driver Licensing laws that require DT as well as parent-supervised driving practice for teens wishing to secure a license before 18. Those licensed before 18 failed the license examination least of all license applicants under 25 and were found to have lower crash rates per 1,000 licensed drivers during the first year of licensure, while18-year-old newly licensed drivers (exempt from young driver license policy) had the highest crash rates of all new drivers under 25 (Walshe et al. 2022). In short, formal and informal training both lead to early licensure and safer outcomes. In terms of mobility equity, unlicensed teens might have greater difficulties accessing certain educational and employment opportunities than their peers who are able to drive (Gao et al. 2022; Handy et al. 2021). Ryerson et al. (2022) found that the network of mostly private driving schools in the Columbus, Ohio MSA are not equitably distributed and introduced the existence of driver training deserts (DTDs), a term that describes Census tracts (CT) with poverty rates and average driving time to the nearest driving school both in the 4th quartile of the MSA; it is possible that teens residing in DTDs have restricted access to DT.

Disparities in access to DT and securing a young driver’s license have safety implications and, if these disparities are disproportionately hurting vulnerable teens, equity implications (Shults, Banerjee, and Perry 2016; Walshe et al. 2022). What remains unknown is whether teens residing in low-income neighborhoods that are also physically separated from DT (i.e., DTDs) are less likely to engage in DT and licensure before 18. We compare teens’ likelihood of completing DT and securing licensure before 18 based on their neighborhoods’ DTD status in the Columbus, Ohio MSA. We hypothesize that teens living in DTDs have lower probabilities of enrolling in DT and securing licensure before 18 than their peers in non-DTDs. We also examine the spatial pattern of the probabilities of enrolling in DT and securing licensure before 18. This study builds upon two previous studies and is enabled by access to a driver licensing database through a partnership between the research team and the Ohio Bureau of Motor Vehicles. In December 2022, Ohio launched Drive to Succeed (currently in a pilot phase) to provide scholarship to low-income teens to complete DT (Office of the Governor 2023). Our findings are helping to inform the distribution of the program to ensure equitable access to DT by teens in low-income neighborhoods.

2. Methods

We use two analyses to examine DT completion and licensure before 18 (DT and licensure, henceforth) between CTs in DTDs and non-DTDs in the Columbus, Ohio MSA.

The first analysis uses the one-tailed t test to examine whether teens residing in CTs classified as DTD have lower probabilities of DT and licensure than those living in non-DTD. DTD status comes from a previous study that classifies CTs in the Columbus MSA into DTD and non-DTD based on the CTs’ poverty rates and physical access to driving school (Ryerson et al. 2022). In the study area, 27 of the 430 CTs are classified as DTD. Predicted individual probabilities of DT and licensure come from a second previous study which uses binomial logit to estimate the probabilities of DT and licensure for 35,771 young drivers between 15.5 and 25 years old in the Columbus MSA (Dong et al. 2023).

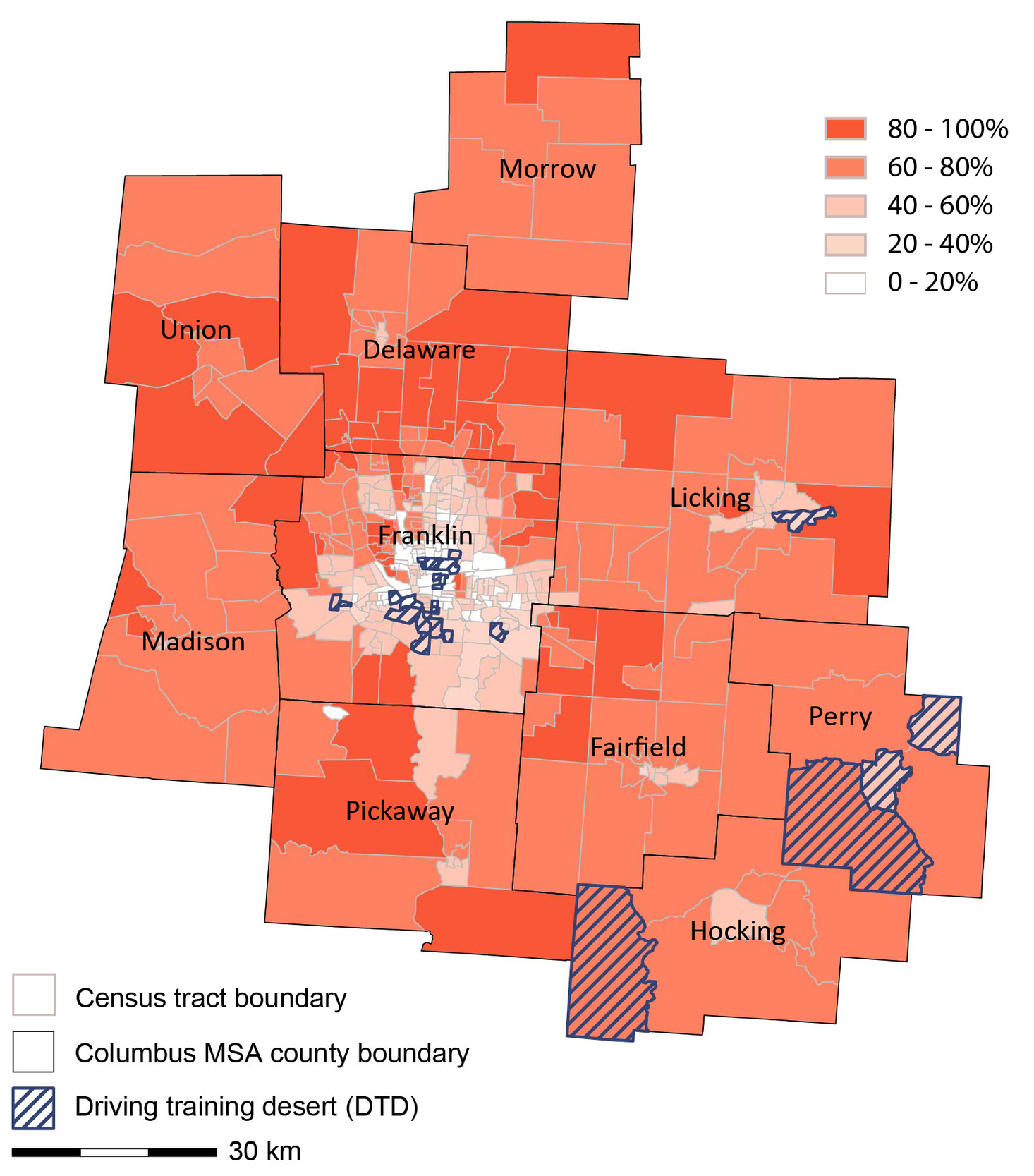

The second analysis uses Moran’s I tests with Queen and Inverse Distance weights to examine whether CTs with similar average probabilities of DT and licensure tend to cluster. Figure 1 visualizes the average probabilities by CT and CTs’ DTD status in the study area.

3. Findings

In support of our hypothesis, the t-test (t = 49.635, p-value = 0.000) shows that on average, individuals residing in DTDs have significantly lower average probabilities of DT and licensure (33.2%) than individuals living in non-DTDs (57.7%). To confirm this finding, we conduct an additional t-test of the observed share of residents under 25 with DT and licensure by CTs’ DTD status. Results (t = 6.003, p-value = 0.000) indicate that CTs classified as DTD (23.6%) have a significantly smaller share of residents under 25 with DT and licensure than those classified as non-DTD (46.5%).

The Moran’s I tests (Queen: z-score = 26.181, p = 0.000; Inverse Distance: z-score = 31.666, p-value = 0.000) indicate that there is significant spatial clustering of average probabilities of DT and licensure by CT. CTs with higher average probabilities are located in the more suburban locations outside of the City of Columbus, such as Delaware, Pickaway, and Union Counties (Figure 1). CTs with lower average probabilities are concentrated in or immediately outside of the City of Columbus, as indicated by the lighter color in Figure 1.

While CTs classified as DTD generally have lower average probabilities of DT and licensure, some CTs in Perry and Hocking Counties classified as DTD have relatively high average probabilities of DT and licensure. A few CTs classified as non-DTD have low probabilities of DT and licensure. Qualitative studies are needed to determine the reason for these seemingly contradictory patterns.

This study provides statistical evidence that on average, teens living in DTDs have lower probabilities of DT and licensure before 18. It identifies clusters of CTs with low probabilities of DT and licensure in the Columbus MSA. The findings are helping local authorities prioritize geographic areas for their financial assistance pilot program that aims to improve access to DT and licensure for lower-income teens. The findings also highlight the need for qualitative studies to understand barriers to accessing driver training services. When licensing and DT enrollment data over a longer period become available, researchers should consider conducting longitudinal analyses to explore whether DTDs lead to lower demand for DT, or vice versa.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Ohio Department of Public Safety partners in this work who provided the licensing data and valuable insights for interpreting the findings. Research reported in this publication is supported by the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) through the Ohio Traffic Safety Office (OTSO) and by the Ohio Bureau of Motor Vehicles.