1. Questions

Research among the general population has shown that parked e-scooters are perceived as obstacles (James et al. 2019), and it is common to feel unsafe (Dowdall-Masters 2020; James et al. 2019; Karlsen and Bjørnskau 2020). People have stated that the boundaries between e-scooter riders and pedestrians are less clear than between cyclists and pedestrians (Gibson, Curl, and Thompson 2022), which in turn may make people feel that accidents are more likely. In addition, while most e-scooter-related injuries only involve the rider, there are cases where non-riders are injured, typically by being hit by e-scooter riders or by tripping over parked e-scooters (Toofany et al. 2021). Complaints reported in media indicate that e-scooters may be especially problematic for people with visual impairments or impaired mobility (Machlar 2020; Norges Blindeforbund 2020; Te 2019). In line with a relational model of disability, we conceptualize disability as something that emerges in the interaction between individuals and the environment (Lid 2013). In this case, we examine whether e-scooters, both stationary and in use, make urban areas less accessible for people with visual impairment or impaired mobility.

From previous studies, we know that people in Norway with reduced physical functioning make fewer and shorter journeys than others (Gregersen and Flotve 2021). When using public transportation, they are challenged by long distances to public transportation stops, poor accessibility to the stop or station, and problems getting on and off the vehicle they need to use (Nordbakke 2011). However, studies are lacking as to whether e-scooters are associated with poorer accessibility.

This project investigated whether, and how, e-scooters affect the perceived safety in, and accessibility to, urban areas for people with visual impairment or impaired mobility. This is particularly relevant in Norway, where e-scooters can be used on sidewalks and pedestrian streets, as well as on cycle lanes and roadways.

We did this by examining:

-

To what extent are parked e-scooters perceived as an obstacle in urban areas?

-

How safe do the respondents feel when interacting with e-scooter riders?

-

Do the respondents change how, or how much, they use urban areas as a result of e-scooters?

2. Methods

We conducted two surveys during September-October 2022. First, a telephone survey among members of the Norwegian Association of the Blind and Partially Sighted (NABP), carried out by Norstat (N =1381). A response rate of 28% generated 380 complete interviews. Second, an online survey among members of the Norwegian Association of Disabled (NAD) was distributed by email to 6764 persons, as well as on NAD’s social media channels. The social media post had very little effect. In total, 233 people completed the survey, 224 of which were recruited through e-mail (3,3 % response rate). 43 respondents started the survey but dropped out before completion. All invitations made it clear that the survey was about e-scooters, likely contributing to people without experiences with e-scooters not participating. Only people who have traveled in areas with e-scooters were asked about their experiences with e-scooters.

Table 1 shows characteristics of the samples.

The respondents are quite representative of the age distribution in both organizations, and for the gender distribution of NAD (unknown for NABP).

The questionnaires are shown in Supplementary Files 1 and 2.

Two open-ended questions (why do you use more time; why do e-scooters make you drop trips) were analyzed by manually reading through and categorizing the content of the answers. For example, respondents who used the word “fear” in their response have been grouped in one category, “increased fear”, though their exact wording varied.

Responses to closed questions are presented descriptively and as logistic regression results. The logistic regression models examined the relationships between the independent variables: “E-scooters as obstacles”, “Feeling unsafe due to e-scooters”, “Degree of visual impairment” (only NABP), “Wheelchair” (only NAD), “Place=Oslo”, and “Almost hit by e-scooter”, and the outcomes: “Avoiding areas/Dropping trips”, “More time traveling”, and “Feeling unsafe”.

All analyses were adjusted for age, whether the participant had a condition that made it important to avoid falling, and degree of vision or main mode of moving.

A more detailed overview of all the variables is given in Supplementary File 3. As the samples were of limited size, we collapsed some of the categories in the factor variables and used separate models to examine different independent variables.

The analyses were done in SPSS (v 29.0; SPSS: IBM Corp 2022) and R (v 4.2.1; R Core Team 2022).

3. Findings

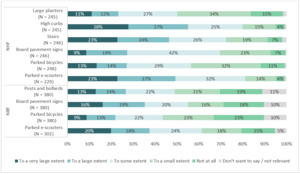

Parked e-scooters are clearly an obstacle for both groups, with many stating that e-scooters hinder them to a large or very large extent, as do other common elements in the urban environment. High curbs and stairs are large obstacles for many people with impaired mobility, while pavement signs and posts and bollards are large obstacles for people with visual impairment.

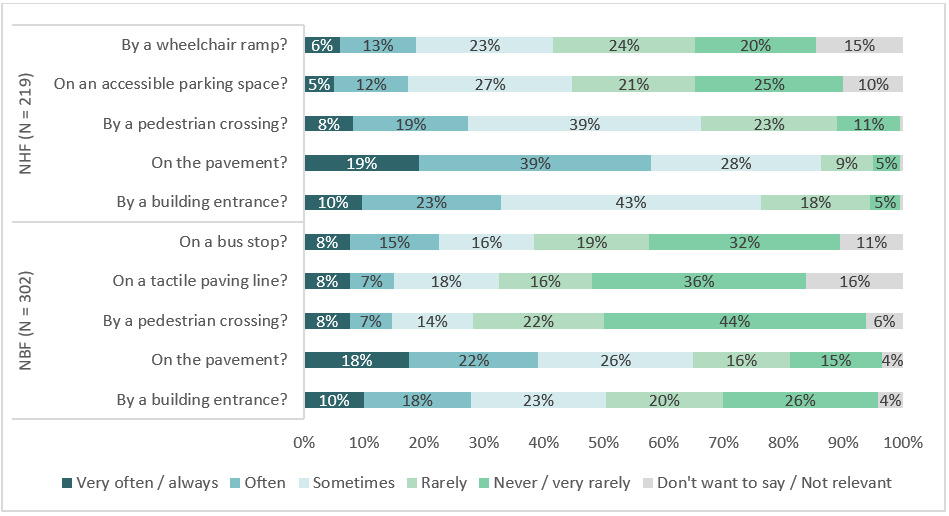

Figure 2 shows that the respondents more often experience parked e-scooters as an obstacle on pavements and at building entrances than on pedestrian crossings or bus stops. Some people are even hindered on, or near, infrastructure elements especially designed to ensure accessibility (e.g. wheelchair ramps, accessible parking spaces or on tactile paving lines).

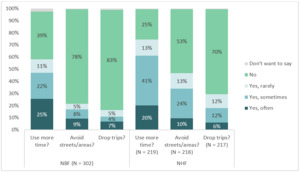

E-scooters impact how, and how much, the respondents travel in urban environments, causing many to use more time on trips, and some to avoid certain areas or whole trips (Figure 3). The open answers showed that uncertainty and fear were the main reasons for avoiding trips for people with visual impairment (based on 49 responses). Fear and cautious walking were the main reasons why trips took longer (based on 176 responses). For people with impaired mobility, the main problems were related to e-scooters as obstacles, which lead to detours, thus causing increased trip duration and frustration (based on 129 responses). Feeling unsafe was an important reason for dropping trips for this group as well (based on 44 responses).

16% (NABP) and 13% (NAD) have experienced falling over a parked e-scooter. 55 % (NABP) and 68 % (NAD) have experienced almost being hit by an e-scooter, and 4% and 17%, respectively, have been hit by an e-scooter. Of the NAD sample, 66% have been forced into the road, and 45% have been forced to turn around, due to a parked e-scooter blocking their path. About two-thirds of both NABP (67 %) and NAD (65 %) members felt unsafe when interacting with e-scooter riders.

For both samples, those experiencing e-scooters as obstacles, or having experienced almost being hit by an e-scooter, were more likely to feel unsafe when encountering e-scooter riders (Table 2). We found no connection between mode of movement (NAD) or degree of visual impairment (NABP), and perceived unsafety.

For both samples, feeling unsafe when interacting with e-scooter riders and perceiving e-scooters as obstacles, were associated with a greater probability of needing more time when traveling, and avoiding areas or dropping trips. There was a tendency for wheelchair users to be more likely to need more time to travel due to e-scooters, compared to people walking.

To sum up, this study shows that many people with visual impairment or impaired mobility experience parked e-scooters as obstacles, particularly on pavements, and they feel unsafe when interacting with e-scooter riders. While there are other common elements, such as high curbs and pavement signs, that also reduce accessibility, e-scooters appear to create more situations where these two groups are disabled by the urban environment.

E-scooters are still a relatively new addition to cities, and current practices for shared e-scooters in Norway have adverse impacts on people with visual impairment or impaired mobility. A holistic perspective on the urban area is needed in order to create urban areas that are truly accessible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to the Norwegian Association of the Blind and Partially Sighted and the Norwegian Association of Disabled for the collaboration on this project, particularly for contributions to the questionnaire design and with recruiting respondents.

FUNDING

Research leading to this publication was funded by the Norwegian Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs’ grant for universal design (nr. 351867).

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests to declare.