RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Residential neighborhoods are a key anchor for daily activities and travel. How transportation infrastructure and accessibility facilitate daily living is crucial to the subjective well-being of individuals (Cao 2016; Ma, Kent, and Mulley 2018; Morris, Mondschein, and Blumenberg 2018). Therefore, it is important to examine the influence of transportation and accessibility on residential neighborhood satisfaction. It is also important to recognize that other neighborhood features (such as social interaction and safety) affect neighborhood satisfaction as well (Cao and Zhang 2016; De Vos, Van Acker, and Witlox 2016; Yin et al. 2016). Understanding the relative role of transportation and accessibility in enhancing neighborhood satisfaction is an intriguing matter. Interestingly, residents living in different types of neighborhoods value different neighborhood characteristics (Cao 2008, 2015). Environmental correlates of neighborhood satisfaction should therefore vary by neighborhood type.

This study applies the gradient boosting decision trees (GBDT) approach to examine the relationship between neighborhood characteristics and neighborhood satisfaction in the Twin Cities. It aims to answer the following questions:

-

How important are transportation infrastructures and accessibility to neighborhood satisfaction?

-

How do urban and suburban residents value neighborhood characteristics differently?

METHODS AND DATA

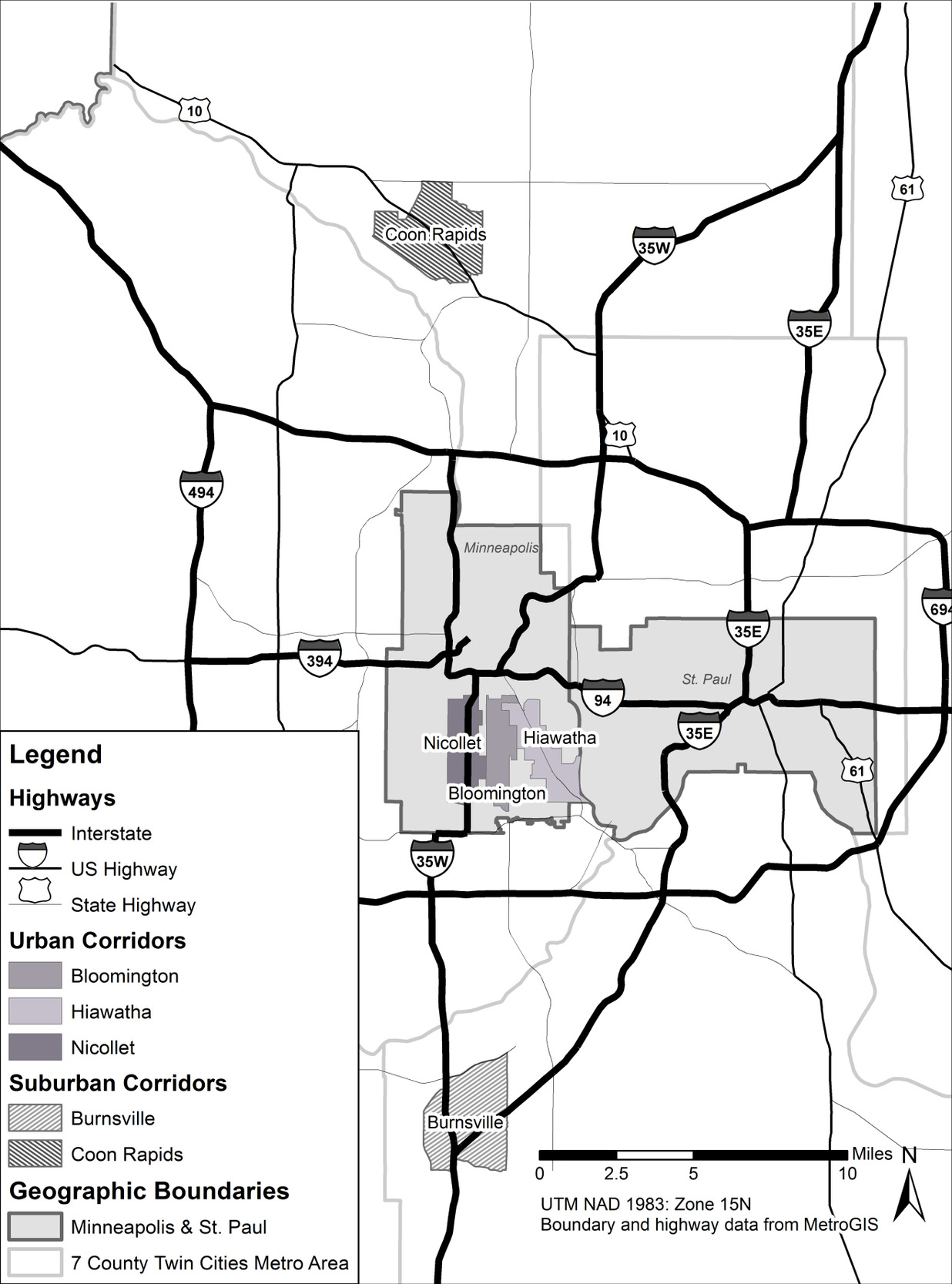

In 2011, we administered a mail-back survey to randomly selected households living in urban and suburban neighborhoods in the Twin Cities (Figure 1). Three urban neighborhoods, mainly developed before World War II, are similar in regional location, street patterns, and transit access. By contrast, curvilinear streets are prevalent and transit services are limited in suburban neighborhoods predominantly developed in the 1970s. There were 1,303 respondents, with a response rate of 22.2%. Among them, 946 live in urban neighborhoods and 357 are from suburban neighborhoods. Refer to Cao and Wang (Cao and Wang 2016) for details on the research design and data collection.

This study uses three sets of variables from the survey:

-

Neighborhood satisfaction. Respondents were asked to indicate how well the characteristics of their neighborhood meet the current needs of their household on a scale ranging from “extremely poorly” (1) to “extremely well” (7). This is the dependent variable.

-

Perceived neighborhood characteristics. Respondents reported how true 30 characteristics are for their current neighborhoods (Table 1) on a scale from “not at all true” (1) to “entirely true” (4).

-

Preferred neighborhood characteristics. We asked respondents to indicate the importance of the 30 characteristics if/when they were looking for a new place to live on a scale from “not at all important” (1) to “extremely important” (4).

If individuals perceived neighborhood characteristics incongruent with their preferences (i.e., the preferences are not met and the characteristics are mismatched), dissatisfaction with neighborhood begins to accumulate (Kahana et al. 2003). Here, we computed mismatched neighborhood characteristics (independent variables in this study) as the difference between perceptions and preferences, respectively.

Utilizing the GBDT approach, we examined the effects of mismatched neighborhood characteristics on neighborhood satisfaction, using the R-based “gbm” package (Ridgeway 2007). The tree-based ensemble can draw on insights and techniques from both statistical and machine learning methods (Friedman 2001). Compared to traditional regression, the GBDT approach has a few advantages in the context of satisfaction studies (Ding, Cao, and Næss 2018; Dong et al. 2019):

-

It produces prediction that is more precise.

-

It does not require data to follow a particular distribution. This feature is particularly useful because most, if not all, satisfaction variables in the literature are skewed to the left.

-

It can accommodate missing variable data. The traditional listwise deletion approach may generate estimation bias if data are not missing completely at random. It also lowers statistical power by reducing sample size (Peugh and Enders 2004).

-

It can address the multicollinearity problem. Multicollinearity could be an issue because some neighborhood characteristics measure a similar dimension of the built environment.

More importantly, the GBDT approach can quantify the relative importance of each independent variable in predicting response, which is a key objective of this study. However, a shortcoming of the GBDT approach is that it does not produce statistical inference.

FINDINGS

Table 1 presents the relative importance of all mismatched neighborhood characteristics to predict neighborhood satisfaction and compares important neighborhood characteristics between urban and suburban neighborhoods. All the relative importance sums to 100%.

Three neighborhood characteristics regarding transportation infrastructure and accessibility are among the top 10 important variables in urban neighborhoods. They are related to bike routes, proximity to workplace, and proximity to religious or civil buildings. By contrast, parking infrastructure is the only transportation and accessibility variable among the top 10 important characteristics in suburban neighborhoods. Overall, transportation- and accessibility-related variables are important to satisfaction with urban neighborhoods, with a collective contribution of more than 30%. However, they have a limited impact on satisfaction with suburban neighborhoods, with a collective contribution of only 12%.

Affordability and crime rate appear in the list of the top five important neighborhood characteristics for both urban and suburban neighborhoods. This highlights their critical role in affecting neighborhood satisfaction. This finding is consistent with the important determinants of residential location choice (Bina, Warburg, and Kockelman 2006; Cao 2008). On the other hand, the relative importance of affordability and crime is substantially different between urban and suburban neighborhoods.

The divergences in influential neighborhood characteristics generally reflects the different conditions of urban and suburban neighborhoods and their residents’ differing needs. Because housing stock is older in urban neighborhoods than in suburban neighborhoods, housing quality and upkeep play a key role in neighborhood satisfaction in urban neighborhoods, more so than in suburban neighborhoods. Furthermore, Minneapolis is well-known for its biking culture and attracts bicyclists to reside there, so bike infrastructure plays an important role. Suburban households have more children than urban households. Accordingly, school quality is more crucial to suburban residents than urban residents.

In summary, urban residents tend to value transportation and accessibility features of residential neighborhoods, whereas suburban residents tend to emphasize affordability, safety, and school features.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Data collection was supported by the Transitway Impact Research Program in the Twin Cities. Jessica Schoner helped with the survey administration and ArcGIS application.