RESEARCH QUESTION AND HYPOTHESES

Transport systems are used on a daily basis by individuals in order to carry out activities such as studying, working, and recreation. The existence of a public transport system should therefore allow all individuals to travel throughout their cities, thus granting everyone the same rights to be a part of society. This should be a right for all citizens regardless of their physical and/or socioeconomic condition. Unfortunately, not all individuals have the same facility to move; in every city there is a significant population of people with physical, psychosocial, cognitive, and sensory disabilities.

Individuals with disabilities are frequently classified as one of the most socially secluded segments of the population due to their reduced mobility (Barnes and Mercer 2005; Aarhaug and Elvebakk 2015), and their difficulties with using public transport is one of the most relevant causes (Kenyon, Lyons, and Rafferty 2002; Field, Jette, and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Disability in America 2007). Therefore, a public transport system that does not allow them to move comfortably and rapidly is a system that excludes them from participating in society. This puts them at a disadvantage, as they cannot adequately pursue all their personal and professional endeavors (Tyler 2009).

Disability can be understood in two different ways depending on which model is used: the medical model or the social model. The medical model reduces the problems of individuals with disabilities to problems of medical prevention, cure, or rehabilitation (Shakespeare 2010). In this model, the difficulty is attributed to the individual and is independent of their relationship with the environment. The social model, on the other hand, understands that disability is influenced by the way in which society is configured, not allowing this population to perform their activities freely (Shakespeare 2010). Under this perspective, the term “person in a situation of disability” is more appropriate because it considers disability as something transitory that can disappear with a change in society. This study will assume this last definition since it is a more humane and less restrictive approach when analyzing the problems of disability in public transport.

The objective of this article is to analyze the current situation for people with disabilities in Transantiago, the public transport in Santiago, Chile. The study focuses on measuring and understanding the difference in travel times between individuals with and without disabilities in the morning peak period (7:30 a.m. to 9:30 a.m.).

METHODS AND DATA

Due to the lack of accessibility studies in public transport in Santiago, two Universal Accessibility Surveys of Transport Modes were conducted in 2016 and 2017. Their purpose was to empirically measure the travel time difference for individuals with and without disabilities in the morning peak period, and to investigate the factors behind them. The study consisted of participants traveling from different points of the city to a common point using different modes of transport. For each combination of origin and mode, particpants were as follows: one with blindness, one with reduced mobility, and one without disabilities. For security reasons and to record problems encountered by the participants with disabilities, each was accompanied throughout their journey by an aide (only to interfere in case of emergency).

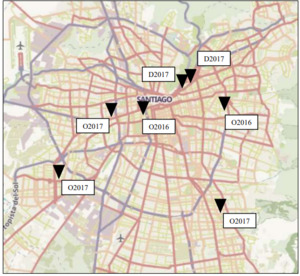

In total, both studies considered five origin–destinations across the city of Santiago, Chile. Travel modes included in the studies were bus, metro, and bus–metro. Figure 1 shows the origins (denoted by O201X) and destinations (denoted by D201X) for both studies. From each origin there were individuals with and without reduced mobility performing the trip on each mode in order to compare travel times across modes for participants without disabilities, with reduced mobility, and with blindness.

FINDINGS

The difference in average travel times for individuals with and without disabilities was 30%, approximately 18 additional minutes. For individuals with blindness the difference was 35%, 20 additional minutes. The relative differences (in terms of percentages) do not vary significantly across origin–destinations, but the absolute differences increase with the distance. The average differences in travel times are presented in Table 1.

There was a greater difference in travel times for participants who made their trip by bus–metro. This is mainly explained by the transfers involved, particularly having to change levels. This is especially complex for people with blindness, because when they get off the first mode they have to identify their location before moving toward the second mode.

When comparing the travel time of the participants who used only bus or only metro, it was observed that the biggest difference appears in metro, which is heavily crowded during the morning peak period. People with reduced mobility require more space to move due to a wheelchair, crutches, or other assistance. People with physical disabilities and with blindness generally move slower than people without disabilities. Therefore, it is expected to be more difficult for them to navigate the platform and the metro station due to the large number of people using the system.

One of the main challenges for people with blindness is dependence on a third party to help them determine which bus lines arrive at the stop, and once aboard the bus to identify when they should get off. Participants mentioned that in many cases those who initially offered to help them board the bus once it arrived boarded their own bus before assisting them (and sometimes did not even tell them). Therefore, people with blindness were left alone at the bus stop without realizing that they were abandoned, requiring another person to help them.

One of the daily challenges faced by people with reduced mobility is the poor condition of sidewalks and roads, affecting their ability to move quickly and comfortably. This increases the likelihood of injury and it prevents them from progressing, especially for those who move in a wheelchair. Intersections are rarely designed properly for those in a wheelchair because the slope to descend from the sidewalk to the street is too steep or in many cases is not there at all. This means that people with reduced mobility must find another longer route to cross the street, increasing their travel time even more.