1. Questions

COVID-19 related restrictions led to a 13% reduction in vehicle miles travelled across Illinois in 2020 (IDOT, 2020), and a 25% reduction in the number of people involved in motor vehicle crashes (MVCs). Still, the proportion of fatal MVCs grew from 0.139% in 2019 to 0.218% of crash victims in 2020. Another 18% of MVCs in 2020 resulted in severely injured motorists, up from the prior four year mean of 11%. Increases in injury severity are also evident in the nearly 72% growth in average hospital charges to over $16k during 2020. The previous four year mean for MVC patients was at just 1.6% growth and less than $10k.

Risky behavior on the part of those involved in MVCs was also elevated in 2020 relative to the prior four years. For the years 2016 through 2019 an average of 3.9% of MVC victims were either un-belted or un-helmeted; that proportion jumped to 6% in 2020. Crashed drivers diagnosed at the hospital as positive for at least one of more than six intoxicating substances ballooned in 2020 to 5.4%, up from the previous four year mean of 2.25%. Crashes in which speeding was a contributing factor were also up in 2020 to 46.3%, relative to the prior four year mean of 43.6%. So while it is clear that risky behavior and severe injury increased on Illinois roadways in 2020, the distribution of crash incidence across sociodemographic groups is not.

This report therefore uses linked crash and hospital files aided by census data to investigate upon whom in Illinois, broadly speaking, the crash burden befell during stay at home orders.

2. Methods

Upon completion of the data use agreement between the University of Illinois Springfield and the Illinois Departments of Public Health and Transportation, crash and hospital data for the years 2016 through 2020 were acquired and successfully linked. The linkage was accomplished using methods developed in the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Crash Outcome Data Evaluation System program (McGlincy 2021). Using LinkSolv software to complete the linkage, a combination of data fields were identified as those with the highest linkage success rate: county, victim age, crash date, victim date of birth, and victim sex.

As successfully done elsewhere (Doucette et al. 2020), 2020 received treatment group designation in recognition of the natural experiment that transpired following the imposition of stay at home orders. As is common with natural experiments, an interrupted times series analysis is applied to the linked Illinois crash and hospital data for the five years of 2016 through 2020 (Bernal, Cummins, and Gasparrini 2017; Craig et al. 2017). To control for seasonality and other trends that may affect MVC injury outcomes, 12 segmented binary logistic regression models stratified by race/ethnicity, gender, and the time period in which Illinois’ stay at home order was valid (3/21/20 through 5/29/20) for each year is specified. Six models for the years ending in 2019 with dependent variables taking the binary form of the combination of race/ethnicity (Black, White, and Hispanic) and gender (male or female) are estimated. In a similar way, another six models for the year 2020 using the same combination of dependent variables, plus an interaction term indicative of treatment group designation, are fitted.

3. Findings

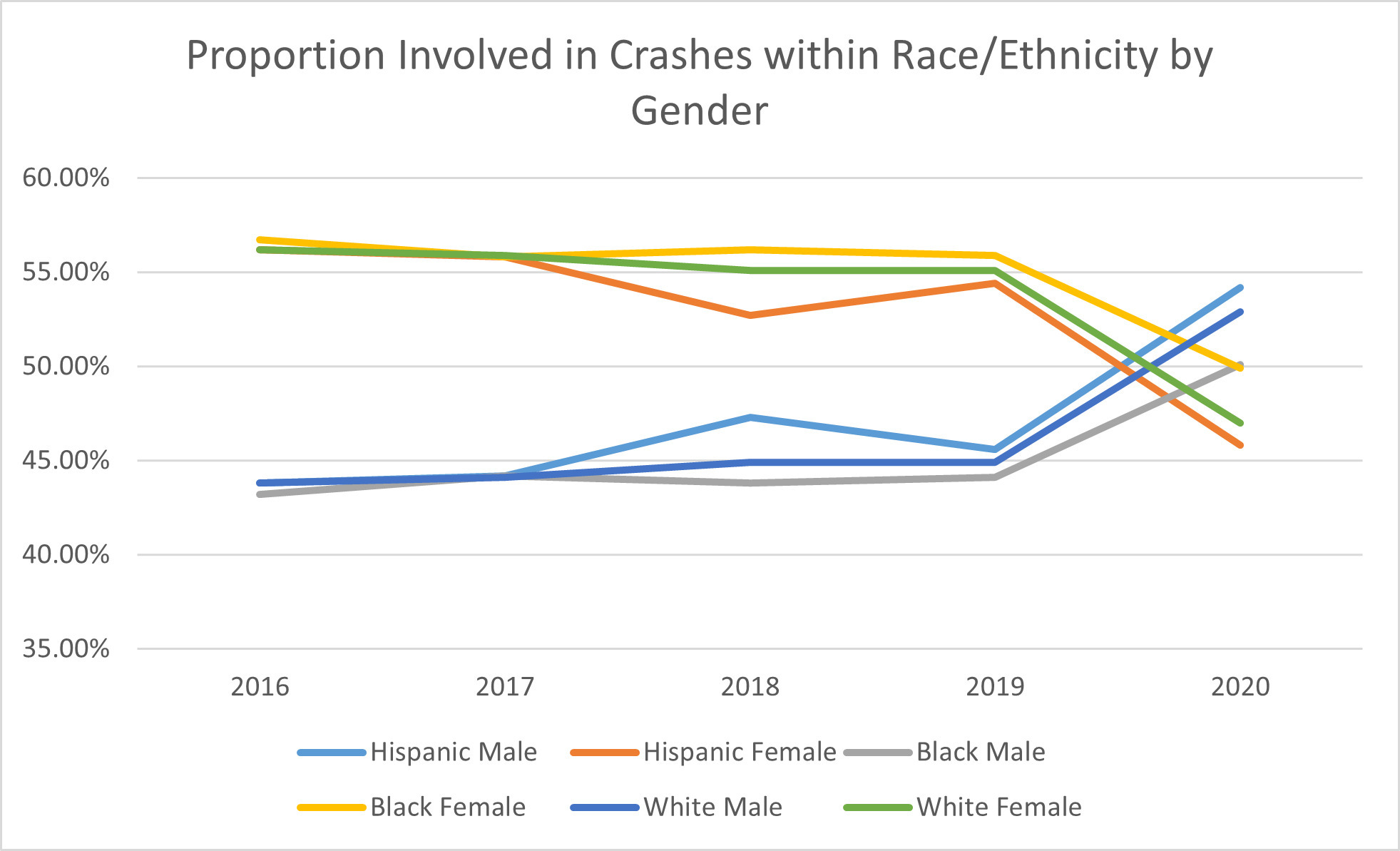

Figure 1 presents some summary statistics of the placebo group, 2016-19, and the treatment group, 2020, during the same stay at home order time period for each year (p < 0.05). The distribution of crash involvement across race/ethnicity and by gender remained relatively consistent in the four years prior to the intervention. During those four years, gender cohort was a better predictor of crash involvement than racial or ethnic categorization. However, crash involvement distribution nearly inverted during the 2020 Illinois stay at home order, with gender cohort affiliation still a strong yet diminished predictor. The female share of Hispanics dropped by about 9 percentage points, the most of any group, followed by an eight percentage point fall by White females.

Figure 2 shows that the median poverty rate of the home zip codes of motorists involved in crashes remained remarkably steady at just below the state average of 11.7% in the four years prior to 2020. Post intervention, the median poverty rate of those involved in crashes climbed more than four percentage points to nearly 15%, similar to other findings (Huang et al. 2020; Lin, Shi, and Li 2021). Motorists from zip codes with poverty rates greater than the state average also increased their share of fatal and severe injury crashes in 2020 from an average of 44% to 49%, and from an average of under 50% to 60%, respectively when compared to previous years (p <0.00). So motorists from zip codes with higher than average poverty rates were disproportionately involved in all MVC types, and they increased their share of fatalities, and they increased their share of severe injuries relative to the prior four year mean.

Table 1 shows the odds ratios of the 12 variables used to study the crash characteristics related to each combination of race/ethnicity and gender (dependent variables). All variables are structured to be binary where a 1 represents an affirmative of the variable name. Odds ratios of greater than one imply an increased likelihood of the dependent variable being true, while those less than one imply a decreased likelihood. Results suggest speeding was a significant predictor of White males being in a MVC during the 2020 stay at home order, where previously it was not, consistent with other speeding studies (Lee, Porr, and Miller 2020; Liao and Lowry 2021; Stiles et al. 2021). Conversely, speeding correlates with a diminished likelihood of White females’ MVC involvement where it did not previously. Severe injury was significantly associated with White males pre and post intervention, while it was only significantly associated with Hispanic males post intervention. Among the strongest associations predicted by the model is the relationship between Black males and females involved in MVCs and above average poverty levels across all years of study.

The above model provides no indication that females changed their behavior as motorists in any significant manner that would lead to fewer crashes. Without evidence of safer behavior, a reasonable assumption could be made that females had a diminished opportunity for crash involvement – perhaps by heeding the stay at home order and driving less. Other factors like dependent care responsibilities, occupation type, and socioeconomic status (Weill et al. 2020) may have also contributed to more females staying home and out of crashes. Much more research is yet needed to better understand how the natural experiment of 2020 impacted life in America and beyond.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to express a debt of gratitude for the team at the Institute for Legal, Legislative, and Policy Studies at the University of Illinois at Springfield. Especially for the technical assistance of Daniel Leonard, M.S., guidance by A.J. Simmons, Ph.D., and manuscript review by Amy Watson. Thank you.

Disclaimer

Funding for this research was made possible (in part) by the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) through funds from the Illinois Department of Transportation (IDOT), 22-0343-03, and/or U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC-RFA-CE21-2101. The views expressed in written conference materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of IDPH, IDOT, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.