1. Questions

This paper explores the impacts on informal settlements arising from COVID-19 measures implemented in Kenya. The Kenyan Government enforced several measures to reduce the spread of COVID-19, including banning public gatherings, working from home, closure of educational institutions and a dusk-to-dawn curfew (Wangari et al. 2021). Public transport was limited to half capacity to maintain physical distance, with passengers required to wear a mask and operators providing hand sanitiser. Motorcycle-taxi operators were required to sanitise passengers’ helmets, while three-wheelers operated on a single-passenger basis (Irandu 2020).

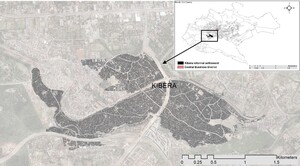

Kibera is the biggest informal settlement of Nairobi, located close to the Central Business District (Figure 1), and characterised by limited access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure, waste management challenges, and exposure to flooding hazards (Mulligan et al. 2019; Njuguna et al. 2013). With population estimates ranging between 300,000 and 1 million people over 2.5 km2, proactive planning is hindered by a lack of reliable demographic data (Taylor et al. 2020), making the implementation of COVID-19 mitigation measures more difficult because of overcrowding and other socio-economic challenges (Quaife et al. 2020).

As a significant settlement with high levels of internal/external journeys to access formal/informal employment, services and goods, predominantly carried out through informal transport options and/or walking, Kibera represents an important case for understanding the mobility impacts of COVID-19 linked with movement restrictions/cessation on different groups living in informal settlements. The study, therefore, seeks to address the following research questions: What were the main changes in mobility experienced by people living in Kibera due to COVID-19? What were the main impacts experienced because of such changes in mobility?

2. Methods

This study uses data collected from ten focus groups involving 62 participants, carried out between August and November 2021. Participants were recruited for two different research projects looking at 1) community severance impacts of the Missing Link#12 bypass in Kibera and 2) mobility needs of Kenyan older people (Table 1). However, given the contextual situation regarding the COVID-19 pandemic, the following questions were asked: “Did the measures implemented to reduce the spread of COVID-19 affect the way you carried out your activities? And what impacts did they have on your life?”.

The focus groups were recorded and transcribed in Swahili and then translated into English for analysis. A thematic analysis was carried out by clustering an initial set of codes, which were further refined into the final themes and sub-themes (Table 2).

3. Findings

Participants reported travelling mainly to commute to work, purchase/sell goods for their small-scale businesses, and shopping purposes. Most participants walk or use a combination of different modes, typically walking combined with minibus and/or motorcycle-taxis.

COVID-19 measures reduced the number of journeys, access to transport and increased time spent travelling. Main causes of such changes were the increase in costs to travel and the implementation of the dusk-to-dawn curfew. The former was due to transport operators increasing their fares to cover the operating costs with reduced capacity and sanitation provision: “The biggest challenge was the hike in fare, we had to pay double the fare as we had to pay for the empty seats” (FG7 - Older woman, casual worker). Moreover, the purchase of face masks required to travel was an additional financial burden. The increase in costs led several participants who could not afford the new fares to walk longer distances to save money and/or find cheaper alternatives: “We were forced to walk a long distance, to get cheaper means of transport” (FG7 - Woman, casual worker).

The curfew forced people to change their time of travelling, creating challenges in coping with new travel schedules. Those travelling by minibus experienced reduced access to transport options and safety issues associated with overcrowded conditions at pick-up/dropoff points: “Despite the half capacity and the hike in fare, people were still scrambling for space in the matatu [minibus], mostly during curfew hours” (FG8 - Businesswoman). The overzealous behaviour of police patrolling the roads in enforcing the curfew was also found to be problematic (Table 2).

The COVID-19 measures had an impact mainly on participants’ income and work, reduced their access to livelihoods and other opportunities. The curfew affected businesses operating during evenings, resulting in significant loss of income, when not leading to the complete cessation of the business: “When COVID arrived, my business was affected due to the curfew. It was operating during evening, so I lost customers and the profit went down” (FG5 - Older man, businessman). Businesses particularly affected in this sense were those in the food sector, which also suffered losses of perishable goods (Table 2), and those relying on customers commuters, who had to travel home quickly: “I was affected badly by the curfew since my business depends on these people who are coming from work in the evening, and those are the hours we are forced to close due to the curfew” (FG5 - Older woman, food vendor). Some businesses tried to adapt by modifying their opening hours but nevertheless experienced a loss of customers and income (Table 2). Finally, several small-scale businesses were forced to close permanently because of the costs of travelling to collect new goods/stocks, typically to marketplaces, and the inability to increase their products’ prices (Table 2). A similar consequence was experienced by individuals quitting their job, as the increased costs of commuting were consuming a significant percentage of their salary (Table 2).

Overall, the findings indicate that COVID-19 measures associated with mobility exacerbated significantly the already challenging living conditions of the people living in Kibera. Such findings tally with other Kibera-specific studies of the lockdown showing that self-reported weekly household income declined by 59% relative to the six months preceding the pandemic (Tompsett et al. 2021).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all participants that contributed to this study.

The authors are grateful for funding from The Institute for Global Innovation/ Institute of Advanced Studies (IGI/IAS) of the University of Birmingham, and the Global Challenges Research Fund, which has helped support this project.