Research question and hypothesis

The measures taken by the Dutch government to battle COVID-19 have influenced public life, leaving public transit with ridership loss. This decline in usage today has implications for customer loyalty in the future. Previous studies by Lau et al. (2003) and by Wang (2014) revealed that an epidemic can affect the loyalty of users for at least up to a year after the end of an epidemic. However, the existing literature is mostly about the use of public transportation during an epidemic without considering specific factors that affect users’ intended loyalty, defined as one’s expected future use of public transit. This raises the questions:

- How do the COVID-19 measures implemented across public transit agencies in Utrecht, the Netherlands, influence customer loyalty? And, how does this vary amongst captive, choice, and captive-by-choice transit riders?

Methods and data

The province of Utrecht, being the central mobility hub of the Netherlands, serves as a case study. As a result of COVID-19 and the related measures, public transit use in the Netherlands dropped by 85% on average in April 2020, compared to April 2019 (Translink 2020).

Data was collected for three weeks in May 2020 using an online survey administered by the Province of Utrecht and designed by the authors of this study in collaboration with Moventem, a local consulting firm. Approximately 50% of the respondents were recruited through a panel; the other half responded to the survey through the Province’s website and social media outlets. A total of 829 valid responses were collected from inhabitants of the province. The survey asked participants to report their pre-COVID-19 travel behavior and their expected post-pandemic public transit usage. Respondents were also asked to express their opinions about transit-related COVID-19 policy measures, the degree to which they experienced fear related to becoming infected, and their perceived service quality before the pandemic. Additionally, respondents reported several sociodemographic characteristics such as gender, age and occupation.

The sample was analyzed in two ways. Firstly, the data from transit users and non-users (non-frequent users without expectations about their future transit use) was analyzed altogether. Secondly, the sample was reduced to only those who used public transit as their main mode (see: Table 1). This group was divided into three types of public transit users, derived from Krizek and El-Geneidy (2007) and Van Lierop and El-Geneidy (2016):

-

Captive: do not have the resources to own a car; depend on public transit.

-

Choice: do own a car, but choose to use public transit as the main mode of travel.

-

Captive-by-choice: do have the resources to own a car, but choose not to buy one and rely on public transit.

Findings

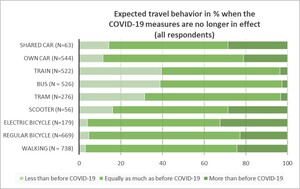

The majority of the survey respondents expect to use certain travel modes less frequently than in pre-COVID-19 times. Figure 1 shows the expected travel behavior when the COVID-19 measures are no longer in effect. Especially electric bicycles (n = 58, [32.4%]), shared cars (n = 18, [28.6%]) and scooters (n = 16, [28.6%]) are expected to be used more often. In contrast, trains (n = 206, [39.5%]), buses (n = 204, [38.8%]) and trams (n = 87, [31.5%]) are expected to be used less often; only a few respondents expect to use public transit more frequently.

These results also differ among the three different groups of frequent transit users. For example, train (n = 89, [34.1%]), bus (n = 87, [33.1%]) and tram (n = 34, [24.3%]) are also the travel modes that are often expected to be used less. However, there is a strong differentiation among the captive, choice and captive-by-choice users. This is especially the case for choice users, who expect to travel by public transit the least. In this group, 40.0% expects to use a shared car more often and 39.4% expects to travel more often using their own car. Captive and captive-by-choice users do not have the option of traveling with their own car and expect to increase their walking and cycling behavior.

Figure 2 shows the results for transit users only. The results are similar to figure 1, but differences exist in the expected increase of car usage and the use of electric bicycles. There is also a slight difference in the use of regular bicycles, where transit users expect to cycle more often than the average respondent.

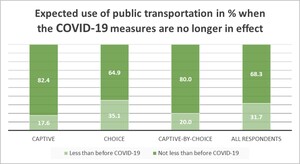

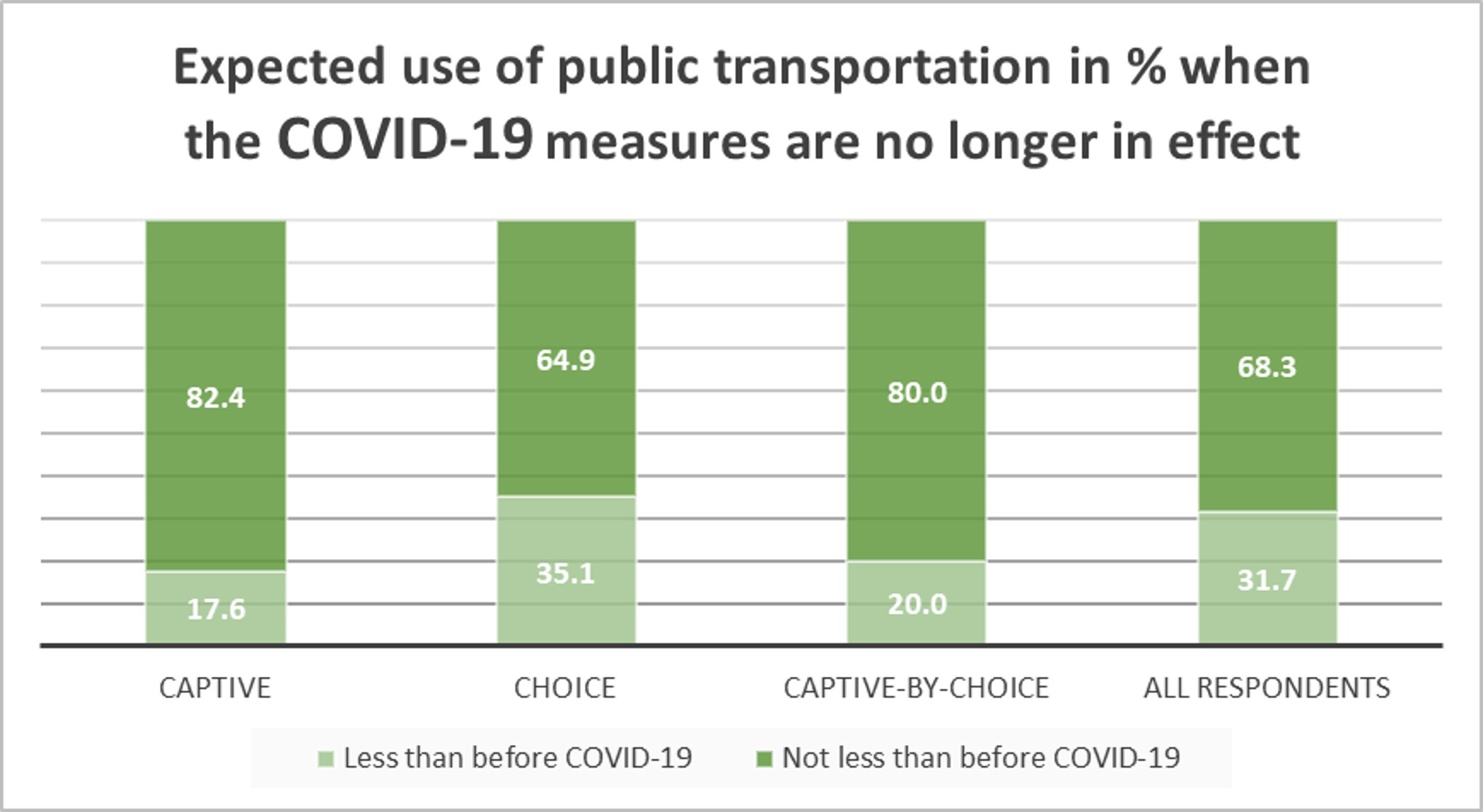

Figure 3 demonstrates that captive and captive-by-choice users expect to reduce their public transit use less than choice users.

Table 1 shows demographic and transportation summary results for the full sample as well as for transit users only. The sample sizes for the models are smaller than the total number of participants due to the fact that in the models only data from respondents who stated their expectations about their future transit use were included. Demographic differences between all of the users and the sub-samples of transit users are expected, such as transit users having a lower average age, different modal distribution, and frequency of use.

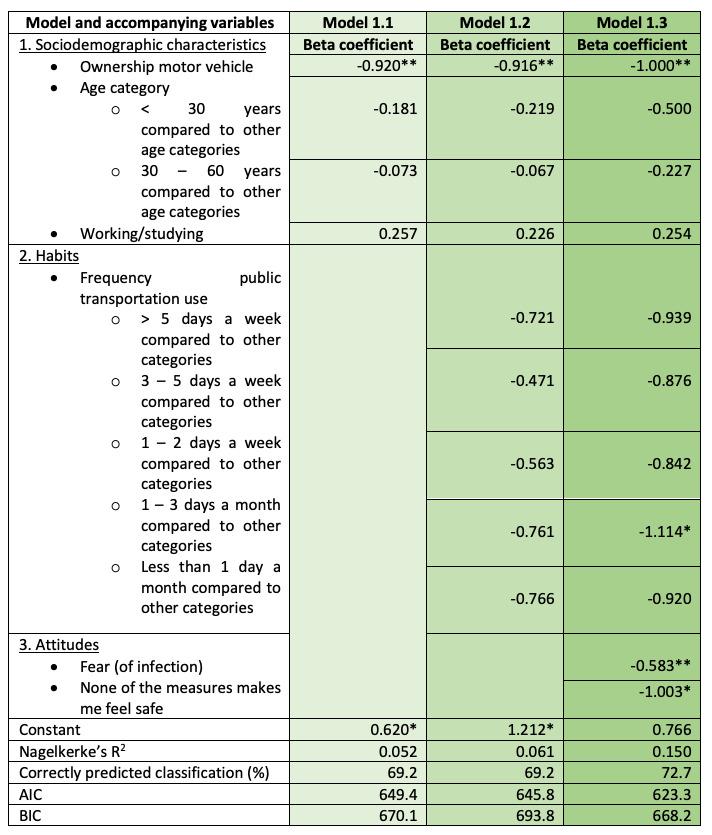

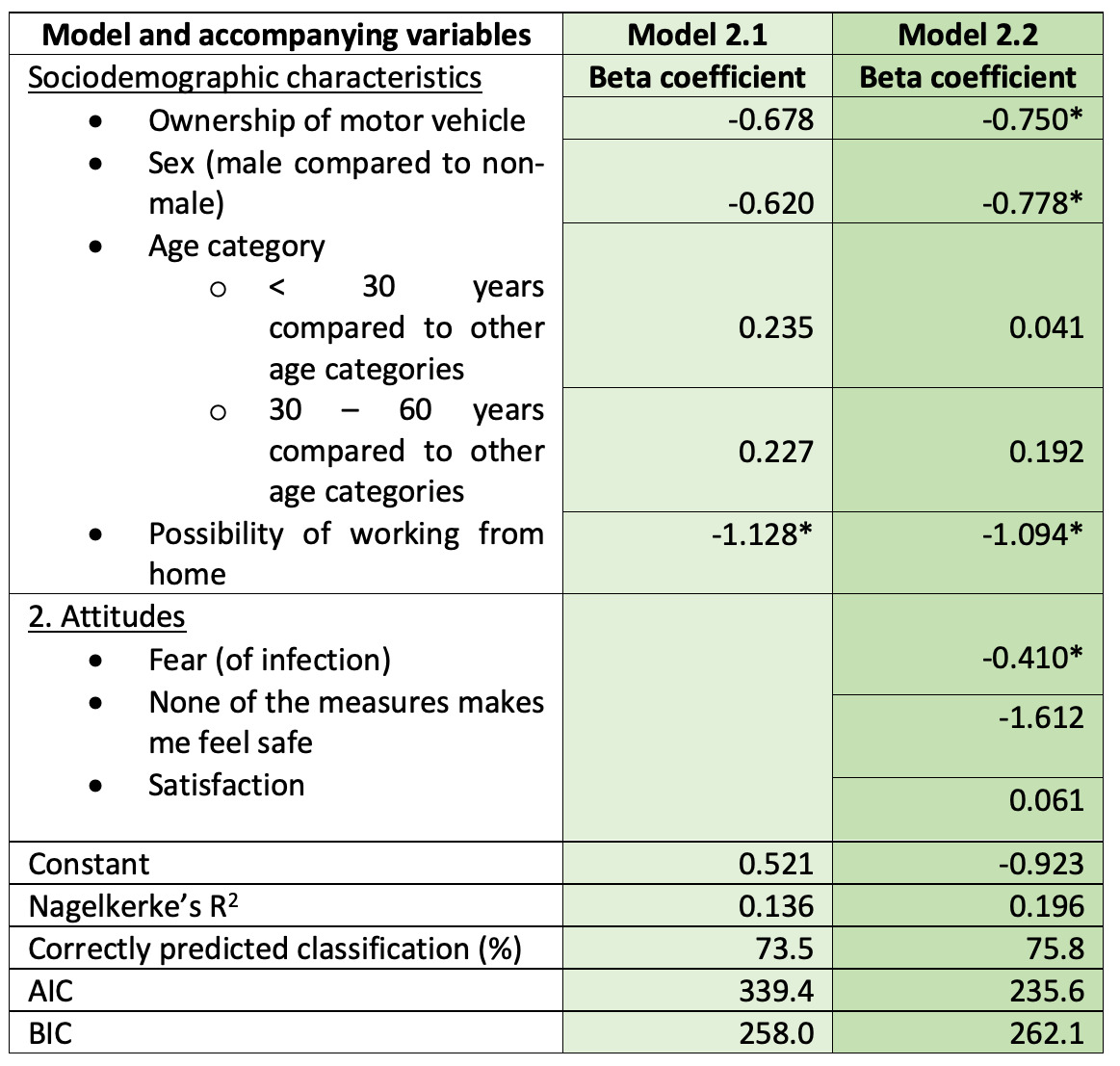

Based on the results of a logistic regression analysis, the factors that may impact loyalty to public transit are shown in table 2 (all respondents) and table 3 (regular, or frequent transit users). Owning a car is significant in both models, as is fear of infection. With regard to the expectation to travel by public transit, the odds of a frequent transit user who owns a car are 75% lower compared to a frequent transit user who does not own a car. This means that car owners are less likely to use public transit, given the circumstances. Similarly, the odds of a frequent transit user to use public transit are 41% lower when they experience fear of infection (model 2.2). Similar results are also observed in the model for all transit users (model 1.3). For all respondents, in addition to this fear, riders who do not perceive any of the taken or suggested measures to be effective in making them feel safe, expect to travel 100% less by public transit. Fear and a sense of safety therefore appear to be highly important factors. Other significant factors are travel frequency, gender and the possibility to work from home.

The frequent transit users model (model 2.2) clearly resonates with the findings from the summary statistics. From the car ownership factor, it can be concluded that there is an expected difference in future loyalty to public transit between the choice users and the groups without car access. When it comes to fear, however, this does not differ significantly between the three groups.

In conclusion, we expect to see changes in travel mode choice in the near future as we begin to recover from the effects of the pandemic. Specifically, we expect an increase in the use of (electric) bicycles, scooters and shared cars and a decrease in the overall usage of public transport. Based on two logistic regression analyses, this change in public transit loyalty is mostly caused by feelings of fear and lack of safety, while car ownership, gender, travel frequency and the possibility of working from home also play a role.

Under pre-COVID-19, or non-pandemic circumstances, travel satisfaction is one of the most important drivers for public transit loyalty (Allen et al. 2019; Carreira et al. 2014; C.-F. Chen 2008; S.-C. Chen 2012; Lai and Chen 2011; Shiftan, Barlach, and Shefer 2015; Widjaja, Astuti, and Manan 2019). However, loyalty in the years 2020 and 2021 is expected to be determined largely by fear and mode availability, meaning that common conceptualizations of public transit loyalty must be revisited during, and directly after, pandemic situations (figure 4).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Province of Utrecht for facilitating this research project. Their input and advice was useful, and their press release about the present study helped to recruit respondents. We are also grateful for the contribution of local consulting firm Moventem, which cooperated in making a comprehensive survey and facilitated the data collection. Finally, we thank the respondents for their time, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback.

_and_a_conceptual_model_based_on_the_result.png)

_and_a_conceptual_model_based_on_the_result.png)