1. Questions

Many past studies have revealed built and road environment factors leading to pedestrian collisions. These include motor vehicles and pedestrians volume, posted speed and street width (Dumbaugh and Rae 2009; Dumbaugh and Zhang 2013; Merlin et al. 2019; Miranda-Moreno et al. 2011; Osama and Sayed 2017). As for individual characteristics, young adults, children, elderly, people with physical limitations and intoxicated people are overrepresented in collisions (Dumbaugh and Rae 2009; Dumbaugh and Zhang 2013; Dai 2012; Ukkusuri 2012). Pedestrian collisions are also more frequent at intersections (Dumbaugh and Rae 2009; Ukkusuri 2012). Traffic signal configuration is thus considered as playing a major role in the prevention of pedestrian collisions. Recent research looking at traffic signal phasing configurations found that lead pedestrian intervals and fully protected phasing seem effective at reducing pedestrian collisions (Fayish and Gross 2010; Houten 2000; Saneinejad and Lo 2015; Stipancic 2020; Zhang 2015).

From a methodological standpoint, collision data are scarce and require many years to collect to offer a representative outlook of collision circumstances (Langbroek 2012; Miranda-Moreno et al. 2007; Theofilatos 2016; Zheng et al. 2014). As such, observed traffic conflict data are useful data for a proactive consideration of road safety issues (Cloutier and Lachapelle 2017; Hydén 1987). The objective of this article is thus to compare two types of traffic signal phasing configuration in two cities with different approaches, controlling for other factors typically associated with traffic interactions with pedestrians at intersections. We expect fully protected phasing to be more effective.

2. Methods

To collect traffic interactions between pedestrians and motor vehicles at intersections, we used a validated non-participatory observation protocol (Cloutier and Lachapelle 2017; Tom and Granié 2011). Figure 1 illustrates the role of the observer (on the left side of the crossing) in determining if the pedestrian (in blue), walking towards the observer, was involved in at least one traffic interaction during his/her crossing. A traffic interaction was recorded when the trajectory of the pedestrian intersected with the perpendicular trajectory of a moving motor vehicle road user (red line in Figure 1), and the distance between the two was estimated by observers to be 2 meters or less.

During data collection, the observer also recorded sociodemographic information on the pedestrian (estimated age group, gender, physical limitation/mobility aid). For each intersection, some characteristics were recorded (one-way, posted speed limit) and volume data from the city open-access dataset were also included in the final dataset. At each intersection, 10 observations were made by two observers to validate interrater reliability with Kappa tests.

The data collection took place during the summer of 2019 on weekdays during three time slots (8-11 AM, 11:30-2:30 PM and 3-6 PM), simultaneously at intersections in Montreal and Quebec City, two cities that use different traffic signal phasing configurations. The City of Montreal mostly uses lead pedestrian intervals, where pedestrians have a head start of a few seconds over vehicles making a turn. Quebec City mostly uses exclusive pedestrian traffic signal phasing, where vehicles are immobilized except for right turn on red light that is permitted at some intersections in Quebec City and forbidden everywhere in Montreal (Quintin et al. 2021). Eighteen intersections (10 in Montreal and 8 in Quebec City) were randomly selected from all intersections with traffic signals in both cities. Selected intersections come from four clusters resulting from a k-means classification computed with 5 variables: presence of a street with a speed limit of 40 km/h or less, number of collisions in a 50 m buffer, presence of a transit stop and population density in a 500 m buffer.

We estimated the relationship between the occurrence of an interaction in a crossing and both individual and intersection-level variables, with our key variable being the type of traffic signal phasing embedded in each city. Table 1 presents the variables included in the model. Using Stata 17, a mixed effect logistic regression was conducted to account for random effects of intersection-level variables (presence of a one-way street, speed limit, pedestrian volume, and motor vehicle volume), fixed effects at the individual level (gender, age group and mobility aid) and our key traffic signal phasing type variable. This variable mostly captures phasing type but could also represent other unobserved differences between cities.

3. Findings

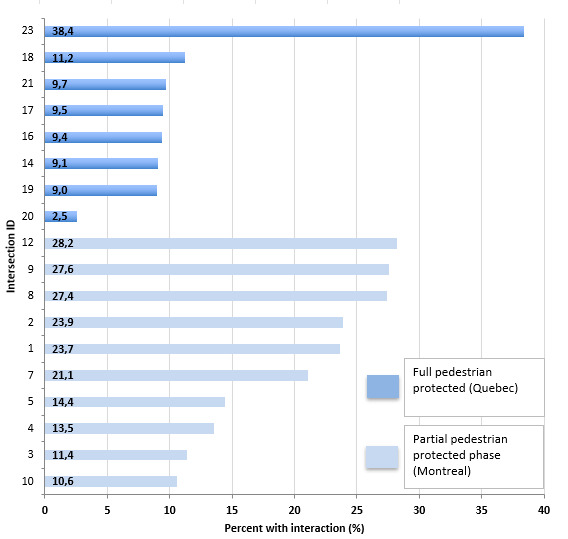

In our sample, 17% of observed crossings involved a traffic interaction between a pedestrian and a motor vehicle (Table 2). The sample is evenly distributed across genders (51% of women) and the adults were the most represented age group (65%), followed by youth (24%) and the elderly (11%). Only 2% of observed pedestrians were using mobility aids. Fully protected pedestrian phasing in Quebec accounts for 38% of observed crossings. Figure 2 shows that we observed far more traffic interactions in Montreal compared to Quebec City and that traffic interaction shares per intersections are more similar within Quebec City (around 9%) than within Montreal (between 10.5% and 28.2%). There are, however, two exceptions in Quebec City where much higher (38%) and much lower (3%) traffic interaction rates are found. The first intersection links an eco-neighborhood, a development that seeks to minimize environmental impact and improve living environment, to a shopping center via a boulevard with bus stops nearby, and the second connects two multilane roads in a low-density neighborhood. We have no strong explanation for these discrepancies based on the available data.

The mixed effect logistic regression model (Table 3) shows a significant inter-class correlation (ICC) of 0.3, meaning that a multilevel model is pertinent and that 30% of the variance in the occurrence of a traffic interaction is explained by the intersection-level variables and the intersection-level random effect. The key policy variable, represented by the fully protected crossing in Quebec, decreased the odds ratio of a traffic interaction by 66.1% compared to the partially protected phasing (OR: 0.339; p=0.002). At the intersection level, an increase of 1000 vehicles per day surprisingly decreased the odds of a traffic interaction by 6.6% (OR: 0.934; p< 0.001). We explain this counter-intuitive result by hypothesizing that intersections with higher vehicle volumes are generally larger, which decreases the perceived safety and leads to more cautious behavior among both drivers and pedestrians. On the other hand, an increase of 1 km/h in the average posted speed limit at the intersection increases the odds of a traffic interaction by 5.3% (OR: 1.053; p=0.036). At the individual level, gender and age group aren’t statistically significant, but the use of mobility aid increases by 2.2 times the odds of being involved in a traffic interaction (OR: 2.205; p=0.036).

Fully protected pedestrian phase in Quebec City are associated with reduced traffic interactions by more than half when considering all other intersections and individual-level variables. Once considering traffic signal phasing, other built environment characteristics at the intersection level are more important predictors of traffic interactions involving a pedestrian than individual level characteristics, but variance between intersections is quite important. This suggests that who crosses and other features of the environment drive part of the observed outcome. Pedestrians using mobility aid seem at greater risk of interactions and would need to be analyzed in further detail. Other factors could lead to a better understanding of the occurrence of traffic interactions at intersections, including, for example, waiting time for pedestrians and dangerous behaviors by drivers. Differences in interactions based on phasing type warrant an exploration of actual collision risks based on these phasing types.

Acknowledgements

We thank the students involved in collecting the data over the summer of 2019, the NGO Accès Transports Viables with whom we received funding from Mitacs (Project IT12315), and the INRS Summer Internship program that provided additional funding for this project.

_while.jpeg)

_while.jpeg)