1. Questions

Good data on unhoused struck pedestrians are tough to come by. Yet states and localities are highly interested in knowing the role the unhoused play in the record-setting pace of pedestrian crashes following the COVID onset. Those data that do exist are typically dependent upon fatal crashes, since these are primarily the purview of readily accessible federal clearinghouses. Though clearly important, a narrow focus on fatalities omits consequential details that could work to improve pedestrian safety.

Research has shown unhoused pedestrians to be at a much greater risk of death compared to all other populations both directly (Hickox et al. 2014) and indirectly (Kockelman et al. 2022). Many note chemical intoxication among the victims as a significant contributing factor (Hickox et al. 2014; Parajuli et al. 2024; Scott et al. 2022). Others cite the darkness of night and poor walking infrastructure (Ferenchak and Abadi 2024; Topolovec-Vranic et al. 2014; Wilson 2022).

The question asked here then is, among surviving unhoused struck pedestrians, what are recent trends in the following: contributing crash factors, victim demographics, injury severity, and the public burden of associated medical care?

2. Methods

Funded by a grant from the Illinois Department of Public Health in collaboration with the Illinois Department of Transportation and the University of Illinois at Springfield, Illinois crash and hospital records for 2023 were linked. Five fields common to both files were identified as those with the greatest match rate to enable linkage of the entire data set, those matched variables included: crash county, victim age, crash date, victim date of birth, and victim sex. Using the combined data sets SAS was applied to identify ICD-10 social determinants of health code Z59, indicating patient status as generally unhoused. Thirty-five struck unhoused pedestrian cases were isolated, analyzed, and compared to a typical struck pedestrian. Hospital charges related to crashes are not necessarily the final cost of treatment.

3. Findings

Possibly contributing to pre-crash circumstances, and observed excess injury, was the relatively advanced age of the typical unhoused struck pedestrian of almost 50, with 31% aged 60 or older. The average age among the general population of struck pedestrians was almost 37 years, with 27% aged 60 or older.

Some 69% of unhoused struck pedestrians were male, an increase of about seven percentage points over the typical struck pedestrian population. About 51% were White and 26% were Black, representing a four-point increase, and no change, compared to the general population of struck pedestrians, respectively. There were several victims (23%) whose race was identified as “other,” “two or more,” or “declined” – statistically the same as the general struck pedestrian population. Those whose ethnicity was identified as Hispanic made up about 17%, or about six percentage points fewer than the general struck pedestrian population.

Other studies have focused on impairment among the struck unhoused pedestrian as a major contributing crash factor, up to 64% in some cases (Hickox et al. 2014; Parajuli et al. 2024). Though still a significant factor, our sample found that less than a third (29%) tested positive at the hospital for a potentially impairing substance, with cocaine leading the way, followed by opioids, cannabis, and alcohol. Among the general population of struck pedestrians that share was nearly one-eighth as great at 3.8%.

The average score on the maximum abbreviated injury scale (MAIS) of a typical struck person was 1.22, compared to 2.26 for a struck unhoused person. The average injury severity score (ISS) for the unhoused was 10.9, or about three times as severe as the general population of struck pedestrian’s ISS of 3.46. The length of hospital stay (LOS) for a struck unhoused pedestrian, another proxy for injury severity, was 7 days, compared to 1.22 for the typical struck pedestrian.

Controlling for injury severity, those higher hospital charges are significantly correlated (p<.001) with LOS of the unhoused victim. Each day in the hospital is correlated with about $10,600 in additional charges, commonly billed to public insurance. For the 35 cases in 2023 that we were able to link between data sets, the total charge for medical care was $4,656,666.90, or about $133,000 per person; $3,901,006.54 (84%) of which was billed to either Medicaid or Medicare. The other 16% of charges were billed to either “other” or “self-pay,” with an additional $562,051 billed to public insurance listed as “Payer 2.” The per person charge for the general population of struck pedestrians was $42,641.32, or about one-third as much.

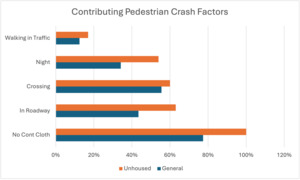

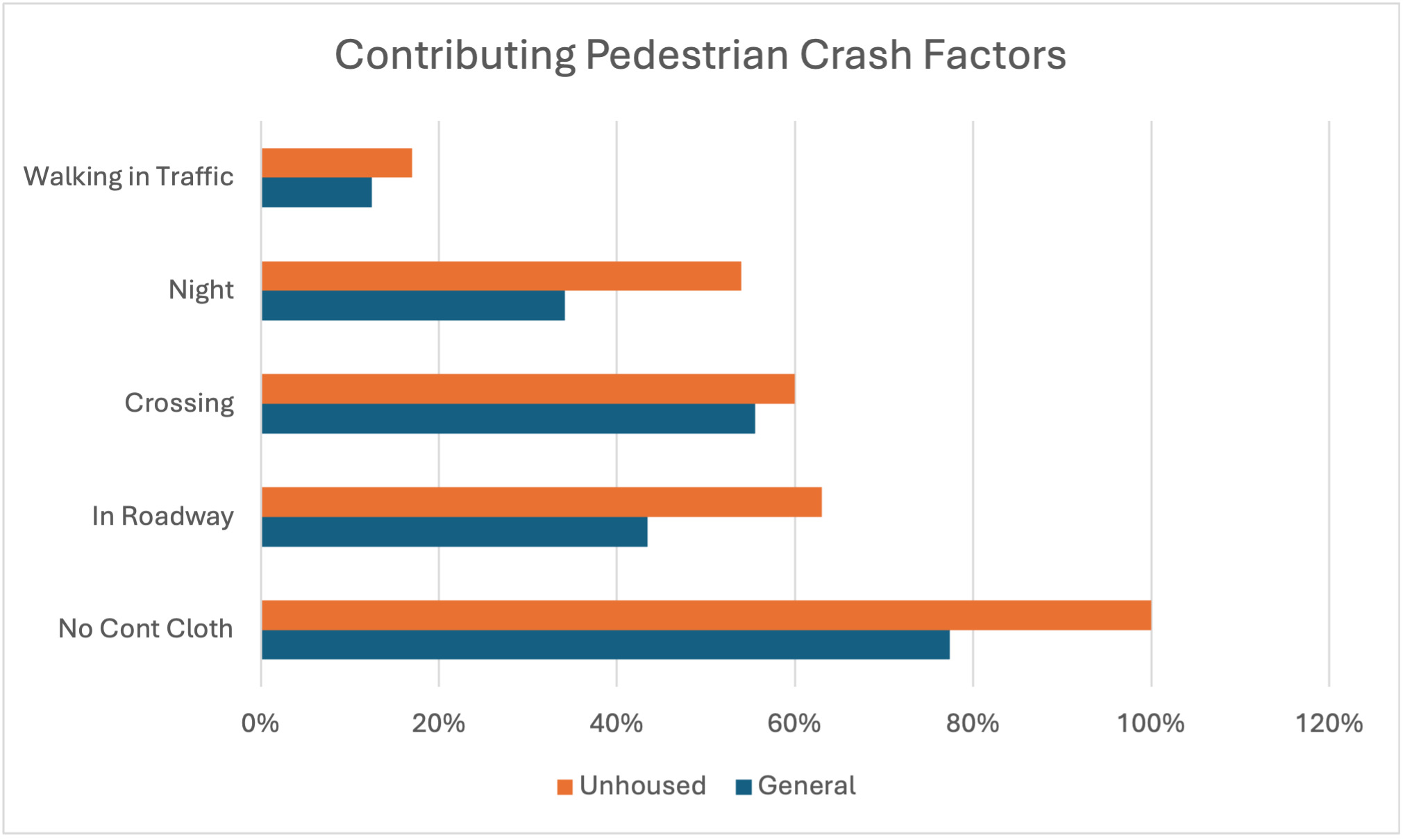

An important contributing crash factor seems to be surrounding conditions, both of nature and built environment. Some 54% happened at night, and about 63% of cases reported the unhoused person as being in the roadway when struck. All of the remaining cases, but for those marked as unknown, indicate the unhoused person on some other part of the road when struck, like: on roadside, in crosswalk, or on the shoulder. Some 60% were recorded as crossing the road in some fashion, another 17% as walking in traffic, and 100% were noted as not wearing contrasting clothing–though it is unclear what would qualify as contrasting clothing. Finally, crashes occurring at night were more injurious for the unhoused pedestrian compared to similar daytime crashes, with an average ISS 1.5 points higher.

With nighttime as a clearly significant contributing crash factor, combined with the unhoused pedestrian being struck in or near the street absent contrasting clothing, a simple, low-cost, and quickly implemented infrastructure solution may be to improve street lighting. Longer-term solutions may be aligning with USDOT’s Safe System Approach and strategic, consistent investment in pedestrian infrastructure.