Research question and hypothesis

This paper gives some first insights into the ability of the participants of different socio-economic groups to accommodate the massive restrictions in the transport supply and activity possibilities resulting from the special measures to limit the spread of the corona virus. On March 16th 2020 Switzerland implemented regulations closing all non-essential service and industrial facilities until further notice. The residents were asked for forgo all travel, except for essential work, medical care, or grocery shopping. Solitary or small-group exercise was not explicitly forbidden, but many public areas were closed by the local authorities to stop the congregation of larger groups. Public transport services were either suspended or massively reduced in frequency.

The speed of the doubling of the number of cases had fallen to 26 days by April 11th and to less then 1 percent per day by May 1st. The Federal government is reviewing the restrictions weekly, but a first easing was implemented on April 27th with more easing after May 11th.

While the federal government has access to unpublished GSM-based analyses on the movements of the residents, only the graphs published by Google[1] and the results of an on-going commercial tracking study undertaken by the local Intervista market research firm[2] are public.

The MOBIS-COVID study aims to trace and explain the changes and understand the differences between persons and locations. The hypothesis is that the mobility adjustments will vary between different socio-economic groups within the Swiss population. In particular, we focus on the impacts by income, gender and accessibility by home location.

Methods and data

A consortium consisting of researchers from ETH Zürich, University of Basel and the Zürcher Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften (ZHAW) is conducting the MOBIS study: https://www.ivt.ethz.ch/en/research/mobis.html. In Autumn 2019 an eight week GPS-tracking study of 3700 persons was undertaken to assess the size of the behavioural impact of mobility pricing in Switzerland. We noted that about 250 of the 3700 participants voluntarily continued with the tracking after the MOBIS data collection was complete. In mid March we re-invited the remaining participants to reactivate the tracking app we had used Catch-my-Day developed by Motion-Tag, Berlin. A total of 1610 have re-installed the app and resumed tracking, as far as we can tell given the absence of movement of many of the participants. The app records all out-doors movements, divides the stream of GPS points into stages and trips, and imputes the travel modes. The respondents can verify the imputation and can add a trip purpose. We had encouraged the respondents to do so, but it was not obligatory.

The original sample had focused on persons who stated that they are using both cars and public transport for their daily travel. For the recruitment we limited ourselves to the French and German speaking parts of Switzerland, as the efforts involved in recruiting from the Italian speaking portion of the population (9%) was deemed disproportionate. Our sample generally matches the known socio-demographics of Switzerland, even without re-weighting. The daily and weekly counts have been normalised to account for the varying sample size as participants re-activated the tracking.

Findings

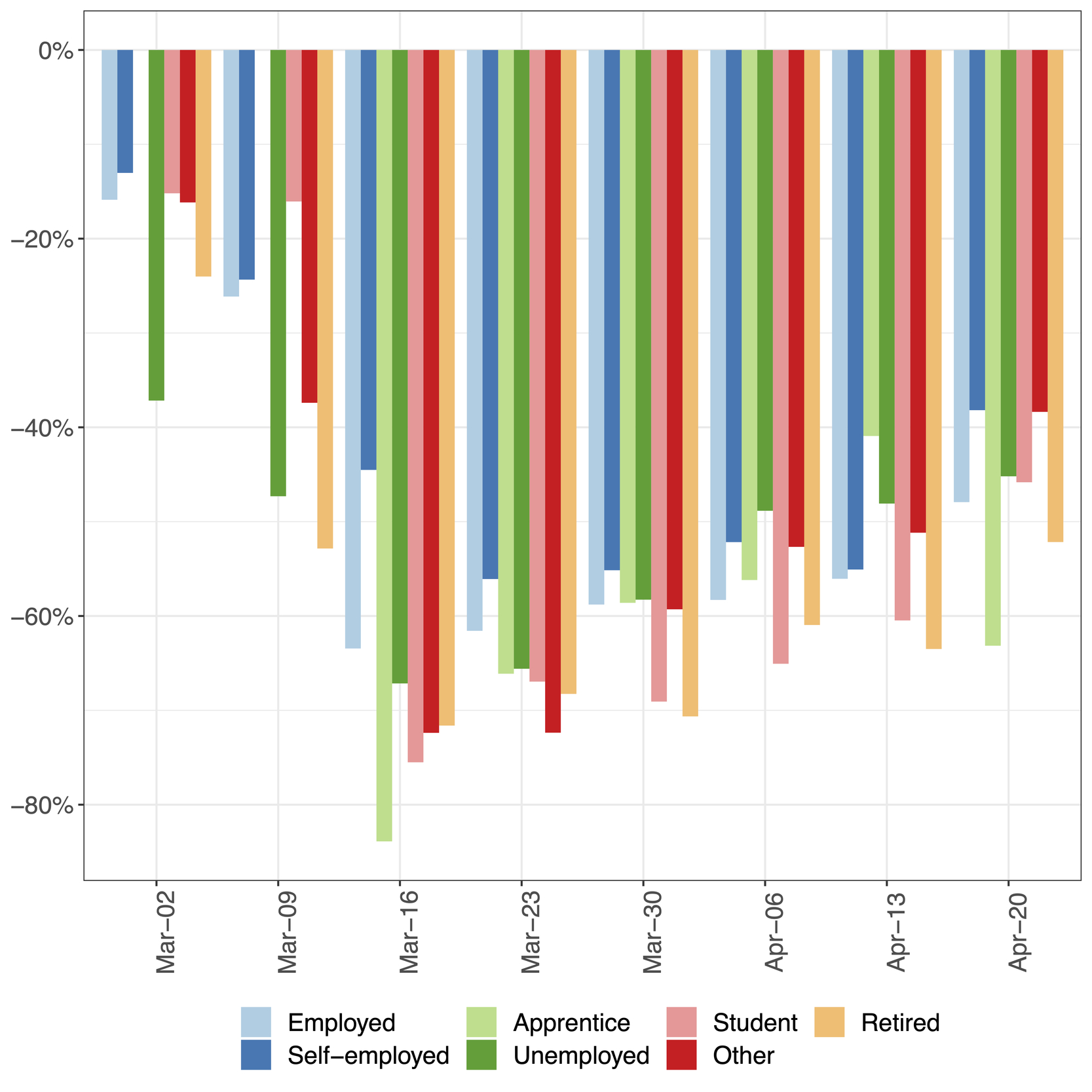

We present a first set of results highlighting some first insights from the data. The focus will be on the changes for participants by their income and by the basic accessibility of their home locations. Table 1 compares our sample with socio-demographics of the last national travel diary in 2015, but note in particular the difference between the studies with regards to the employment status, i.e. being employed, in an apprenticeship or being self-employed.

The comparison with the population representative Intervista panel in Fig. 1 shows that our panel matches it in its response. In advance of the lock-down the distance travelled was decreasing, but the effect of its imposition is clearly visible in that week. In the following weeks travel rebounds with a dip for the Easter weekend. Males continue to travel more than the females in both studies. The differences between the studies become much smaller under the constrained conditions.

The general level of accessibility of the home location influences the total kilometers travelled and the reductions observed during the lockdown, as seen in Fig. 3. In the before period we see clear differences by accesibility-quintiles of the home locations, which become less pronounced in the restricted period.

The activity space is a convenient summary measure of the range and scope of the activities of the persons (See Schönfelder and Axhausen (2010)). These collapse together with the number of trips per days, but more so. The number of trips per workday shrink to 60% of their previous about 5 trips per day, and the activity spaces to 20% of their previous size, as seen in Table 2. Trip duration remains relatively constant except for bicycle use, with difference between genders (Table 3). Striking is the increase in bicycle use. We have compared the trend against the numbers of last national travel diary and see that this increase is above and beyond the usual increase in spring time. Further analysis, not shown here, reveals that the increase is due to weekend afternoon use, suggesting a clear sporting, fitness, leisure motivation.

Formal modelling of these behaviours, especially to see if there is a change in the preference structures, will begin with the end of the restrictions. It will be interesting to see, firstly, how different socio-economic groups respond, and if this shock is able to break routines or if they will reassert themselves again.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the willingness of the 1610 volunteers who continue to track themselves allowing us to understand in detail the impact of the Sars-CoV-2 crisis on Swiss travel behaviour. This work is a spin-off of the MOBIS project funded by SCEER and the Swiss Federal Office of Roads, which also provided some extra funding for this unexpected continuation for which we are especially thankful. The results and their interpretations are our own.

The contribution of the full MOBIS team is very much appreciated. The reviewers’ comments helped to improve the paper substantially. All remaining errors are our own.

published together with other statistics by the Kanton Zürich (https://statistik.zh.ch/internet/justiz_inneres/statistik/de/covid19.html