1. Questions

By shifting traffic away from cars, cargo bikes can significantly contribute to a sustainable mobility sector (Bissel and Becker 2024a). This is particularly relevant in urban areas, where the challenges of car-dominated transport, such as air pollution, are more pronounced, and everyday trips are of shorter average distances. Hence, urban areas serve as test fields for mobility innovations (Carracedo and Mostofi 2022; Gruber, Kihm, and Lenz 2014; Hess and Schubert 2019).

In recent years, various types of cargo bike sharing operators have emerged. These include socially innovative, community-driven grassroot initiatives (commons cargo bikes) and commercial new mobility start-ups (Becker and Rudolf 2018). Whereas the latter operate similarly to traditional free-floating bike sharing systems, the former do not charge fixed fees and collaborate with local shops and other hosts to organize the rental process (Bissel and Becker 2024b).

While research on cargo bike sharing is limited (Hess and Schubert 2019; Riggs 2016), previous research on car sharing underscores the need to investigate differences between operating modes (Kolleck 2021). Against this background, this study addresses the research question of how cargo bike sharing operator types differ in terms of user demographics and behavior.

2. Methods

As a pioneer city with the largest number of mobility providers in Europe (Gersch, Bartnik, and Genseler 2021), Berlin offers ideal conditions for this study. Among them are the largest commons cargo bike initiative (Bissel and Becker 2024b) and commercial cargo bike sharing operators (Carracedo and Mostofi 2022). This unique combination allows for the analysis of comparable datasets.

More precisely, the study compares data from two surveys. The commons cargo bike initiative “fLotte Berlin” collected and provided the first dataset (“Commons”: N = 101). The present study compares these data with results from a second survey (Weber, Steiner, and Werner 2022). This data stems from “Avocargo” users (“Commercial”: N = 130), a commercial cargo bike sharing operator active in Berlin from 2021 to 2023.

The survey period for both studies was in November 2021, using a very similar questionnaire and methodology. Both surveys covered questions on socio-demographics, mobility habits, and user behavior (e.g., trip purposes with cargo bikes and substituted transport mode). The Supplemental Material provides additional information.

3. Findings

User demographics

Table 1 shows a similar average age and household size among users of both operator types. Respondents are, on average, slightly younger than the Berlin average of 42.5 years (Berlin-Brandenburg Statistics Office 2024). In addition, the user demographics of commons cargo bikes are less male-dominated compared to commercial cargo bike sharing, with the gender distribution matching the Berlin population (Berlin-Brandenburg Statistics Office 2024). Notably, commons cargo bike users have less frequently access to cars, while commercial users are characterized by a higher proportion of households with children.

Usage reasons

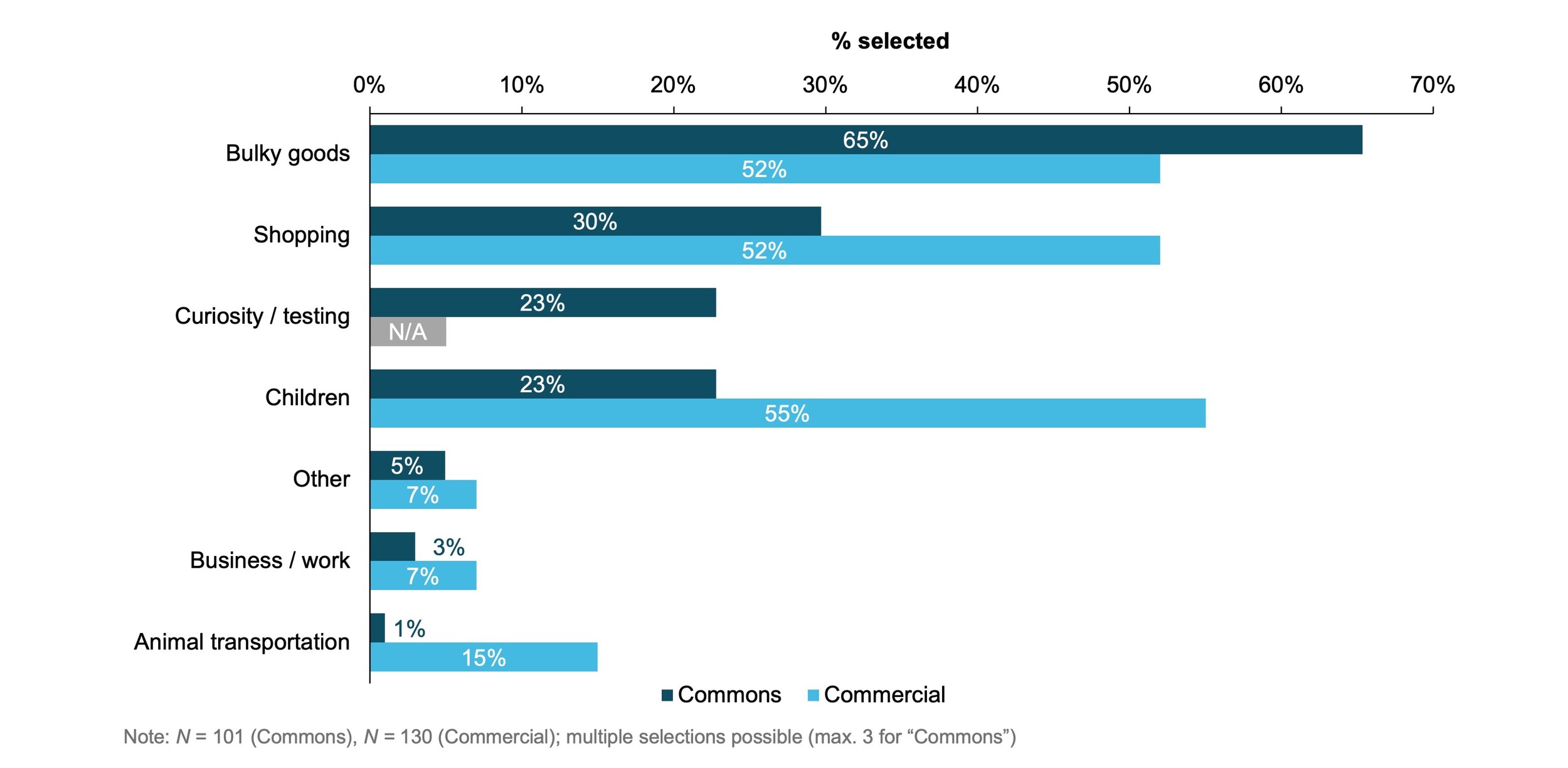

Figure 1 indicates that cargo bikes provided by both types of operators are often used for transporting bulky goods and for shopping. For commercial cargo bike sharing, transporting children and shopping are more prevalent compared to commons cargo bike users. Conversely, in line with the commons cargo bikes concept (Bissel and Becker 2024b), “testing” cargo bikes is a frequent use case for this operator type. In the commercial survey, this usage reason is included in “Other”.

Substitution of transport modes

Figure 2 highlights the high potential of both cargo bike sharing operator types to substitute car trips in urban areas. Additionally, 17% of commons cargo bike users would not have undertaken the trip at all, emphasizing the role of this operator type in testing and expanding mobility options.

Purchase intentions

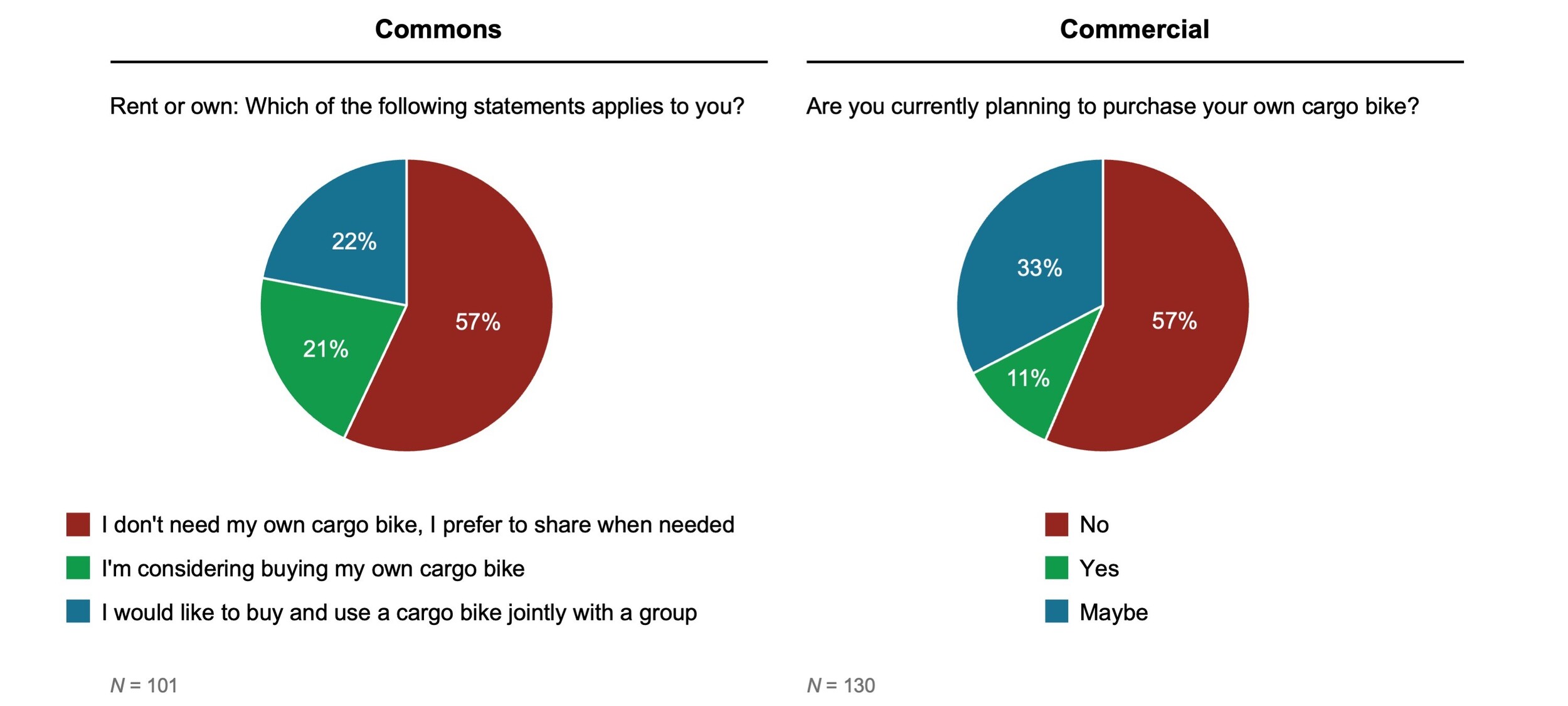

As illustrated in Figure 3, more than half (57%) of users of both operator types do not intend to purchase their own cargo bike. This implies that cargo bike sharing can not only substitute car trips and complement other transport modes, but also provide an alternative to costly cargo bike ownership.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that various cargo bike sharing operator types can positively impact urban areas by substituting car traffic. Differences in user demographics and behavior suggest that both types can complement each other in achieving the overarching goal of sustainable urban mobility. This finding is supported by the modest overlap in user groups, with only 20% of commercial cargo bike sharing users also using commons cargo bikes (Weber, Steiner, and Werner 2022).

Suggestions for explaining the high share of women among commons cargo bike users are provided by Bissel and Becker (2024b). The gender distribution of commercial cargo bike sharing is, in contrast, similar to findings from previous research on (cargo) bike sharing (Carracedo and Mostofi 2022; Dill and McNeil 2021; Fishman et al. 2014). Notably, while women were found to use cargo bikes more often for transporting children than men (Bissel and Becker 2024b), this use case is more prevalent for commercial cargo bike sharing, despite the lower share of women.

Limitations and future research

While this study draws on two similar surveys conducted in the same city and time period, further research is required to validate these findings. For example, the discrepancy in the number of children per household may be partly due to slight differences in item formulation. Similarly, differences in transport purposes could be influenced by the question formats. Therefore, future research should employ identical questionnaires and larger, potentially more representative samples.

In addition, future research could investigate the robustness and underlying root causes of differences in terms of transport purposes. This also includes determining the relative impact of different characteristics (e.g., price and rental process). For instance, research could test the hypothesis that parents prefer automated handover for regular trips. Finally, evaluating other forms of cargo bike sharing operators (e.g., regional public transport providers), more comprehensive socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., income) as well as additional indicators (e.g., average utilization of cargo bikes) could represent promising avenues for future research.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the fLotte Berlin team for collecting and providing the data. Financial support by the Foundation of German Business (sdw) is acknowledged.