1. Questions

A growing number of young children attend center-based child care (care provided by professionals in a licensed child care facility), potentially increasing child care travel. Despite this increase, there is relatively little research on child care travel and, in particular, its intersection with sex. Previous research shows sex differences in travel behavior, largely a consequence of gendered roles both within and outside of the home. We hypothesize that child care travel is similarly differentiated. We expect women to be more likely to make child care trips than men (as the broader literature on the gender division in household-serving travel suggests), and we expect the dominance of women making such trips to influence the mode by which these trips are taken and the travel distance in relation to home and (for working parents) to their workplace.

2. Data and Methods

The analysis focuses on adults in households with young children in California. We rely on publicly-available and confidential spatial data from the California “Add-On” of the 2017 National Household Travel Survey (NHTS) and confidential data from the California Department of Social Services (CDSS) on child care facilities licensed and open between 2010 and 2020. The 2017 NHTS data include information on the characteristics of trips and households and the latitudes/longitudes and location names of trip origins/destinations. The child care facilities data include facility type, date of opening and (if applicable) closing, address, and capacity. We analyze only those facilities that were open and licensed during the timeframe in which the 2017 NHTS data were collected.

The 2017 NHTS only includes travel diary data for respondents ages five and older. Therefore, to assemble a dataset of child care trips, we, first, selected the trips of five-year-old that were to “attend childcare.” To identify child care trips involving children under 5, we then identified respondents with children ages 0-4 who made an escort trip (drop off/ pick up someone) and geocoded these trip destinations. We then spatially matched these locations to our geocoded child care facility dataset. We labeled those trips that matched as child care trips and added them to the child care trips of those five and older. This laborious process to identify child care trips likely explains the lack of research on child care travel.

The spatial matching process—the novelty of our research—resulted in 756 child care trips, trips for which the destination is a child care center. These trips constitute less than one percent (0.41%) of all trips on the travel day. We use these data to examine the role of sex in three aspects of child care travel: trip making, travel mode, and travel distance from home and workplace.

3. Findings

Figure 1 shows that women make almost 70 percent of all child care trips. While child care travel is significantly differentiated by sex, women are slightly less responsible for child care and other escort trips than other household-supporting trips. For example, women make almost 80 percent of trips to buy services and about 75 percent of trips to buy goods and meals.

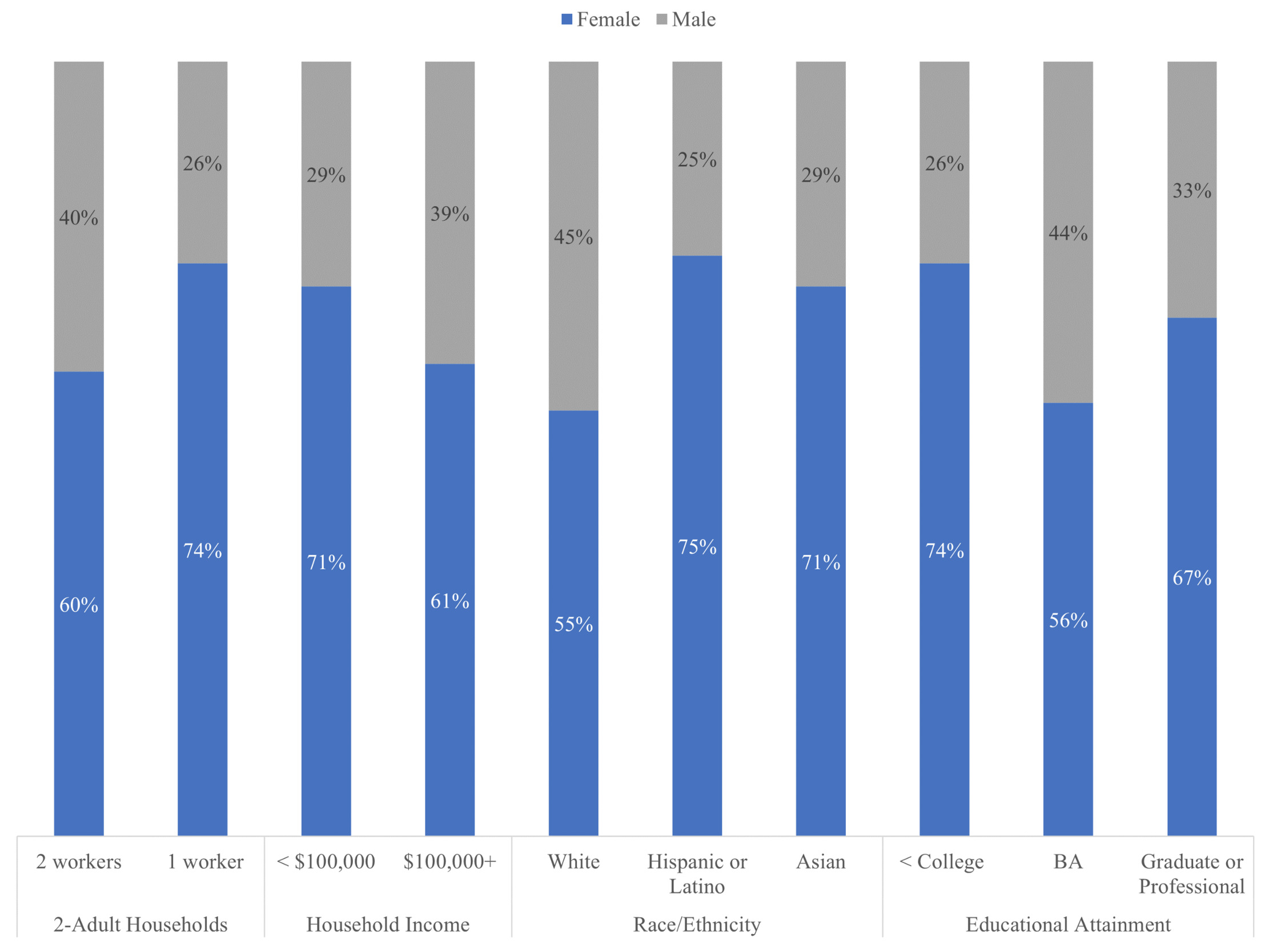

Figure 2 shows that women are more likely than men to be responsible for escorting their children to child care regardless of the number of household workers, household income, race/ethnicity, or educational attainment, a finding similar to that of escort trips in general (Han, Kim, and Timmermans 2019). However, the sex composition of child care trips is least balanced among Hispanic or Latino adults, adults with less than a college degree, and adults in two-adult-one-worker households (in which men are more likely than women to be employed). In contrast, they are most balanced among adults in white, two-adult-two-worker households, and among individuals with a bachelor’s degree.

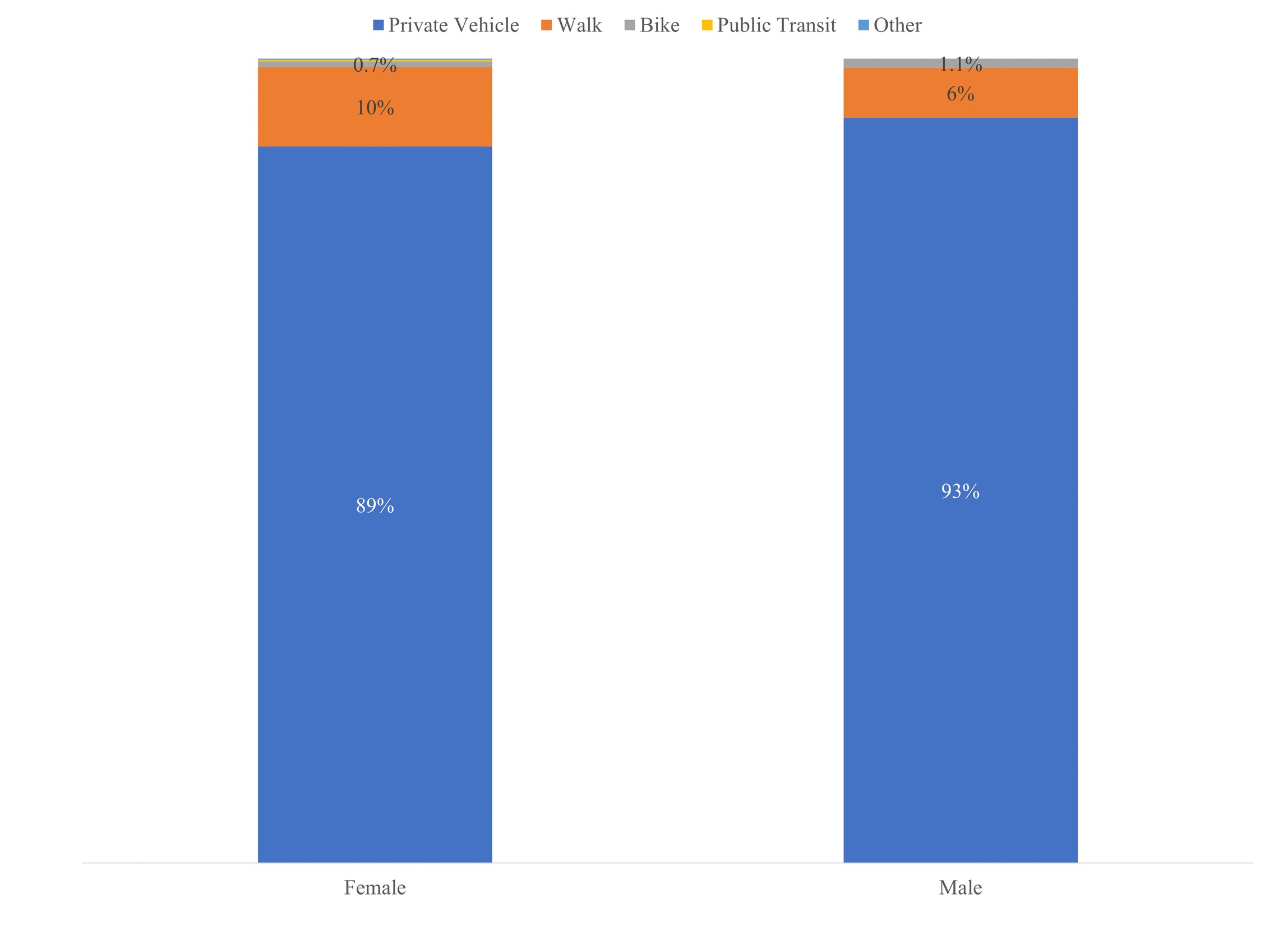

The vast majority of child care trips are made in a private vehicle. Compared to other modes, private vehicles better enable travel with passengers (and their cargo) as well as complicated travel patterns such as child escort trips (Habib, Anik, and Robertson 2021; Hensher and Reyes 2000). The second largest child care trip mode is walking, suggesting that many adults take advantage of child care centers located in close proximity to their homes. Bike, transit, and other modes combined comprise about one percent of all child care trips. As Figure 3 shows, compared to men, women are slightly less likely to make child care trips in a personal vehicle and more likely to walk with their children to and from child care centers.

Among households with at least one worker, families tend to send their children to centers located closer to their homes than to their workplaces. This finding holds true regardless of the number and sex of household workers. However, the mean home-to-childcare distance is substantially longer for two-worker households compared to one-worker households. Consistent with other studies, our data show that commute distances for women with young children are 34 percent shorter than commute distances for men.

Home-to-childcare distance for households in which women are the sole workers is slightly longer than for households in which men are the sole workers. When men are the sole workers in the household, home-to-childcare distance is the shortest; indeed, women in such households make 82 percent of these child care trips.