1. Questions

Teleworking presumably reduces the need for office building space, which in the US currently accounts for 17% of the commercial building floor space and 16% of commercial building energy use (EIA 2018). There has been a gradual long-term increase in teleworking (Phoung et al. 2024). A rapid surge in teleworking during COVID-19 (O’Brien and Aliabadi 2020) highlighted its significance for the economy in general and for energy demand in office, residential, and transportation sectors. Given the continued popularity of teleworking, one expects it will drive reduced demand for office building space in years to come. By quantifying the relationship between telework and office building space, we can anticipate changes in the real estate market and inform urban planning. There are implications for energy demand as well: teleworkers tend to use more energy at home and less in offices and transportation, but its effect on office building space is poorly understood (Phoung et al. 2024). These considerations motivate the driving question of this paper:

What effect has telework had on the area of office building space in the US?

2. Methods

We address the research question by building a regression model to explain historical office building space based on the number of office workers and teleworkers. Historical office building space is available from the CoStar database (CoStar Group 2023). The number of office workers indicates total demand for offices and is estimated by combining our estimates of the share of office jobs based on O*NET (USDOL/ETA 2023) with data on the number of employees in Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics (OEWS) (BLS 2023b). Increases in the number of teleworkers, which is taken from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS) (BLS 2023a), drives down demand for office buildings. The number of (full-time) teleworkers is computed by identifying the respondents who work from home and then deleting the hybrid teleworkers who work both from home and at an office (Phoung et al. 2024). Figure 1 shows the logic connecting the data sources to processed variables for the regression model.

The key challenge is how to construct variables for the regression model given data constraints. The CoStar database tracks historical office building space by location, but not by industry or occupation; i.e., we can differentiate across time and region, but not by industry or occupation. We need corresponding datasets for the number of office workers and teleworkers by year and region. The ATUS and OEWS provides annual data by region, year and for different industries and occupations. The number of office workers variable ought to describe the number of people working in an “office” (a room with desk and computer), whether in an office building or a home office. There is no direct data source describing this for the US, so we construct a dataset by first estimating the fraction of office jobs per industry sector. We use the O*NET database, which provides information on occupational characteristics and requirements nationwide (USDOL/ETA 2023). We identify office workers by screening the survey questionnaires in four O*NET occupational descriptors: Work Activities, Work Context, Skills, and Knowledge. This resulted in defining 30 office worker features that help to distinguish whether an occupation requires an office, such as “Working with Computers”, “Administration and Management”, and “Economics and Accounting” among others. Any occupation with more than 5 of these 30 features is defined as an office occupation. We then combine this list of office occupations with the OEWS dataset that estimates annual employment for about 830 detailed occupations in each major industry sector to produce the proportion of office workers (Table 1).

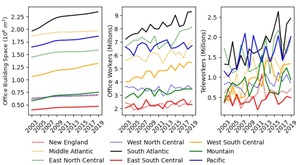

ATUS describes the employment per sector, combining this with Table 1 results yields the number of office workers per year and region. The result is a dataset for the three variables for 2003-2019 for 9 census regions (USCB 2013), generating 153 data points (Figure 2) for the regression model outlined in equation (1).

Ordinary Least Squares regression (OLS) is applied to the following model:

Office Building Spacet+Δ, r (m2)=β0(m2)+β1(m2worker)×# of Office Workerst,r+β2(m2worker)×# of Teleworkerst,r+ ϵ

is the average office building space needed per additional office worker, and is the average influence on office building space per teleworker. is expected to be negative (telework should reduce office building space). The sum + can be interpreted as the “office building space required by teleworkers”. is the error term.

t refers to a year between 2003 and 2019, and r denotes one of 9 census regions in the US. Owing to the fact that the average office lease spans about 3 to 5 years (Fisher and Ciochetti 2007) as well as other time-lagging effects, transitioning an office worker to a teleworker may not have an immediate reduction in office building space. Thus, we expect a delay between the change in number of office workers and teleworkers and the resulting change in office building space utilization. To account for this delay, the regression model includes the time lag Δ ranging from 0 to 6 years.

3. Findings

On average, each office worker requires 32 m2 (340 square feet) of office building space. If an office worker transitions to telework, the required office building space is reduced by an average of 14 m2 (149 square feet).

The regressions (Figure 3) consistently had an R2 value of 0.89 for all time lags. The model shows that the “average office building space required by office workers” is highly significant (p-values < 10-38) with a value of 30 to 32 m2. The p-value of is higher, and varies by time lag (.034-.89). We choose a preferred model with the lowest p-value of (time lag is 5 years), which suggests that the average office building space required by office workers and teleworkers is 32 and 18 m2, respectively. This suggests that shifting an office worker to a teleworker result in an average 44% reduction in office building space (14 m2). While this is a notable reduction, it is much lower than a 100% reduction that might be naively assumed by teleworkers no longer using office building space. There is a need for teleworkers to retain some office building functions, directly for meeting spaces and flexible offices, and indirectly for supporting functions such as payroll, which involves workers in office building space.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation Environmental Sustainability program, grant #2243099.