1. Questions

Numerous studies have focused on the walking behaviors, highlighting attitude as a key determinant (Yu and Zhu 2016). However, the specific factors that shape these attitudes remain less clear, as does the process by which these attitudinal factors influence the decision to walk to the grocery store. Understanding the underlying causes of these attitudes and how they drive behavior will provide valuable insights that can guide initiatives aimed at encouraging more people to walk to the grocery store, thereby promoting healthier and more sustainable transportation habits. This study explores the following questions:

-

What factors influence attitudes towards walking to the grocery store?

-

How these attitudes subsequently affect the decision to walk to the grocery store?

2. Methods

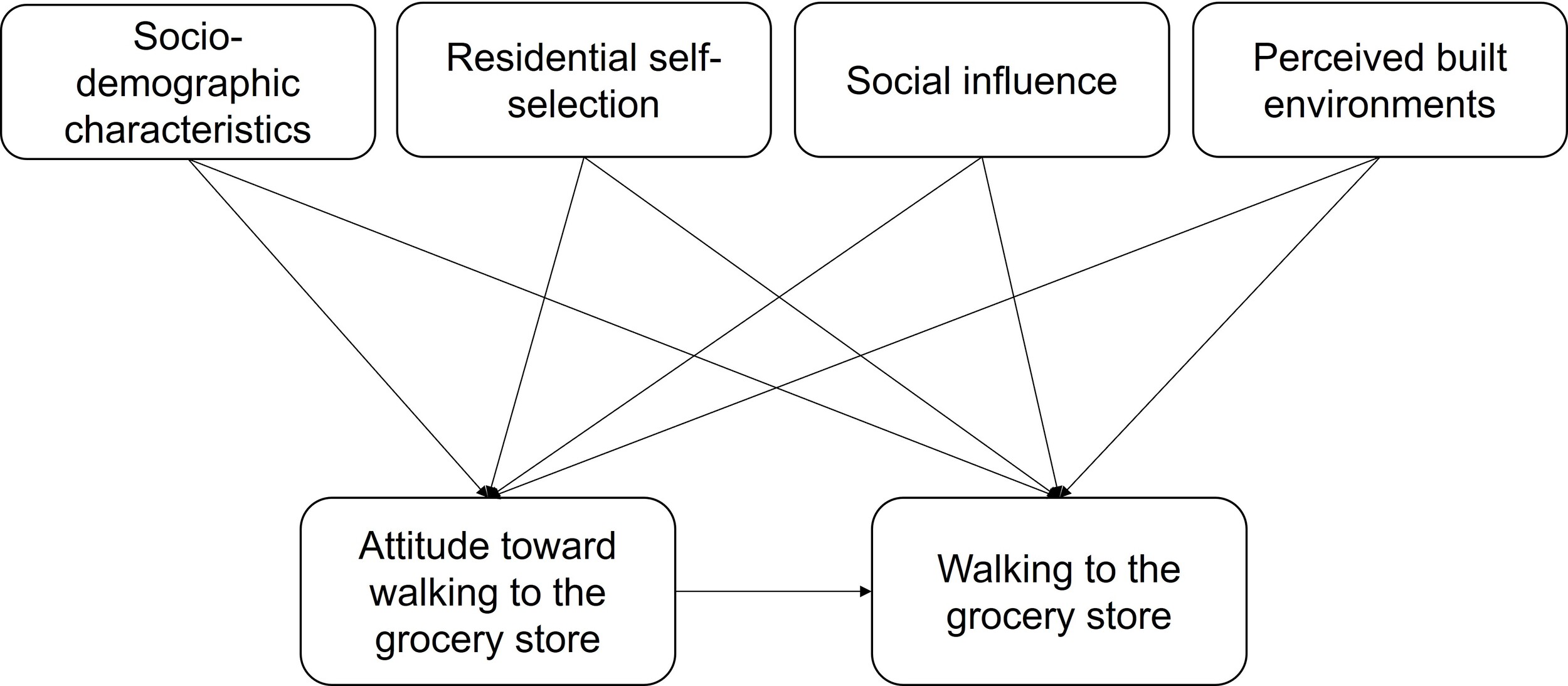

This study proposes a theoretical framework based on existing literature, hypothesizing that (1) five domains—socio-demographics, residential self-selection, social influence, perceived built environments, and attitudes—directly influence the decision to walk to the grocery store, and (2) attitudes mediate the indirect effects of the other four domains (Figure 1).

This study analyzed survey data from 975 adults in Orlando, Florida. Conducted from April to May 2024, the online survey was promoted using QR-coded flyers in Publix grocery stores, social media ads, community boards, and emails from local organizations. Table 1 summarizes the variables, measurements, and descriptive statistics. This study employed a structural equation model (SEM) to examine complex relationships between multiple variables, including direct and indirect effects. SEM is ideal for understanding how attitudinal and environmental factors influence the decision to walk to grocery stores while controlling for confounding variables. Unlike studies using regression models, SEM could reveal both direct and indirect associations that influence walking behavior to grocery stores. Socio-demographic characteristics were included as control variables.

I utilized the statistical software M-Plus 8.5 to test the proposed framework through a two-step process. First, I built measurement models to verify the factor structure of the latent variables. The construction of latent factors, such as positive peer influence, positive attitude and experience, and barriers and concerns, was grounded in theoretical foundations. Second, I tested the structural model to explore the complex relationships among variables. I employed Weighted Least Squares (WLS) estimation in the SEM model because Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation can yield inaccurate test statistics and standard errors when the outcome variable is binary (Brown 2006).

3. Findings

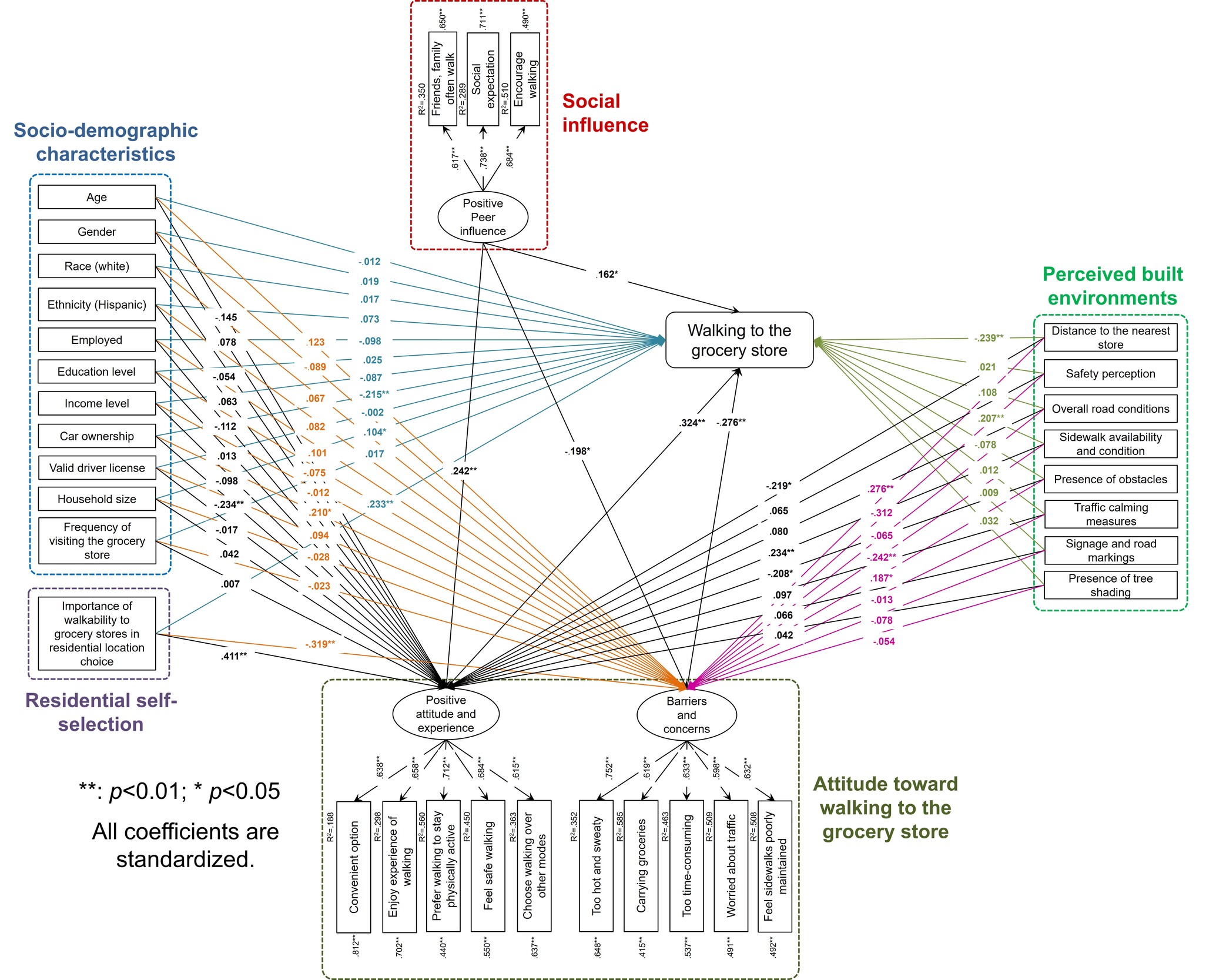

To evaluate the SEM model fit, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is 0.038 (<0.05 indicates good fit), comparative fit index (CFI) is 0.92 (>0.90 indicates good fit), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) is 0.91 (>0.90 indicates good fit). These values indicate that the SEM model constructed provides a good fit with the data (Brown 2006) (Figure 2).

This study found a negative correlation between car ownership and attitudes toward walking (coefficient = -0.234, p = 0.005). Higher car availability reduces the likelihood of choosing active transportation modes (Ding et al. 2018). It illustrates that individuals with easier access to a car are less likely to walk or bike to destinations like grocery stores. Positive peer influence and social support significantly impact attitudes toward walking, which emphasizes the role of supportive social networks in promoting physical activity (Foster and Giles-Corti 2016).

For the mediating effect, several variables (e.g., car ownership, importance of walkability to grocery stores in residential location choice, social influence, distance to the nearest store, sidewalk availability and condition, presence of obstacles) all influenced walking behavior to the grocery store through the mediator of attitudes. Positive attitudes increase the likelihood of walking, even among those who own cars. Conversely, negative perceptions due to obstacles or long distances can deter walking, highlighting the need for supportive environments that promote active transportation choices.

The availability and good condition of sidewalks significantly enhance the likelihood of walking to the grocery store, underscoring the need for pedestrian-friendly pathways. The strong positive correlation between favorable attitudes toward walking and the frequency of walking to the grocery store suggests that when individuals enjoy walking or perceive it as beneficial, they are more likely to choose walking as their mode of transport.

Incorporating objective measurements such as population density and land use mix could offer valuable insights into mode choice. However, this study did not gather detailed data on participants’ residential locations, preventing us from calculating these factors. Future research could benefit from including such measures to enhance the analysis.